Survey: COVID-19 pandemic takes toll on staffing

Responses to the 2021 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey indicate that OR leaders continue to face significant challenges as a result of COVID-19. The survey results come at a time when the buffeting waves of the pandemic are receding for some leaders, leaving them on the shoreline of a post-pandemic world. As health systems focus on right-sizing resources and keeping providers and patients safe, the survey illuminates several notable differences between this year’s responses and the previous couple of years.

Staffing has been particularly hard hit. Nearly half (46%) of respondents lost staff in the past year because of the pandemic, and half reported increased turnover rates for RNs, compared to 22% in 2020 and 34% in 2019. The percentage of OR leaders reporting increased surgical technologist (ST) turnover doubled from 24% last year to 48% this year; that compares to 29% in 2019.

OR leaders also are experiencing headaches related to volume. In all, 44% of respondents reported a decrease in surgical procedure volume in the past 12 months, up from 30% last year and 18% in 2019. Other results illustrate the extent of the pandemic’s negative effects in the past year.

- The average turnover rate was 12% for RNs and 11% for STs, compared to 8% and 7%, respectively, in 2020.

- Nearly half of OR leaders reported increased open full-time equivalent (FTE) positions for RNs (49% vs 30% in 2020 and 37% in 2019) and STs (48% vs 33% in 2020 and 34% in 2019).

- Recruiting experienced OR nurses is more difficult for 75% for OR leaders, up from 63% in 2020.

Both RN and ST staffing are in turmoil. Fewer than half (40%) of OR leaders reported no change in RN turnover rate, and 44% reported no change in ST turnover rate, both considerably lower than the 61% reported in 2020 for each role.

Slightly more than one-third (37%) of respondents reported that the percentage of open positions for RNs stayed the same during the past 12 months, down from 51% in 2020. Only 14% experienced a decrease. Some respondents had either 2 (19%) or 5 to 9 (18%) open RN positions, but 15% had 10 or more. Only 17% reported no open positions.

Less than half (43%) of OR managers reported that the number of open positions for STs stayed the same during the past 12 months, down from 52% in 2020, with 10% reporting a decrease. One-fourth of respondents had no open ST positions, whereas 16% had 1, 16% had 5 to 9, and 9% had 10 or more open positions.

The most common staffing changes in the past 12 months were redeploying staff temporarily to another unit (66%) and loss of staff because of the pandemic (46%) or transfer to another unit (34%). A total of 35% of respondents reported increased use of agency and travel staff. That’s more than double last year’s 14% and higher than the 20% who did so in 2019. A total of 28% of respondents said they eliminated open positions (vs 17% in 2020), and 25% required staff to take time off without pay. Only 14% hired more direct care staff, compared to 36% last year and 40% in 2019.

Recruiting during a pandemic has proved challenging. Nearly two-thirds (61%) of OR leaders say that recruiting STs has been more difficult in the past 12 months, up from 56% in 2020 and 51% in 2019, and only 4% say it has been easier (vs 12% last year and 9% in 2019).

Three-quarters of respondents are finding it difficult to recruit experienced OR nurses, up from 63% last year and 68% in 2019. Only 22% reported recruitment had not changed in the past 12 months. Difficulty in recruiting new or inexperienced OR nurses was reported by 23% of respondents (vs 15% in 2020), and just 15% reported that recruitment was easier (vs 31% in 2020).

When recruiting nurses, most OR leaders (58%) require an associate degree in nursing (ADN). Slightly fewer than half (43%) require a baccalaureate degree in nursing (BSN). Only 12% require certification in perioperative nursing, and 7% require no degree or certification.

Only slightly more than a quarter (26%) of respondents reported an increase in surgical volume in the past 12 months, down from 46% in 2020 and 40% in 2019, with 30% reporting volume had remained the same.

The 220 responses to our question asking OR leaders to share how their organizations are preparing for future pandemics or other disruptive events can be broken down into three broad categories.

Revising response plans. This included updating existing disaster management plans and creating new ones. For example, one OR leader noted that the organization had strengthened its incident command structure. Assessing and creating protocols and policies were part of these efforts, and several respondents mentioned working with external agencies. Other comments included:

- “Building a library of all measures taken during the pandemic to use in adapting emergency and pandemic response plans and keeping historical data for future use.”

- “Emergency management team works to identify required supplies and protocols for disasters based on risk analysis.”

- “Being in a hurricane-prone state, we have long had a disaster plan in place. With respect to pandemics, we’re keeping the well-being of the staff at the forefront of any plans.”

- “We have created playbooks based on changes we made for COVID-19 to help prepare for future pandemics. Discussions are ongoing about additional negative-pressure ORs and inpatient rooms.”

Training and education efforts. These focused on drills and tabletop exercises, but also included emergency response training. For example, one respondent said the organization provided incident command training for all managers.

Supply chain. These comments included increasing inventory of personal protective equipment (PPE); one respondent said the organization had created its own warehouse for supplies. Other comments were:

- “Ensuring storage of disaster supplies, including PPE and equipment.”

- “We are part of a large healthcare system that has looked at the purchase and storage of potential required supplies, and we have made efforts to purchase those required items and then store them in a central location.”

- “Strategic planning for supply chain needs.”

Some respondents provided positive comments about their organizations, such as:

- “We have an effective incident command group that responds to all disasters. It is effective for hurricanes and proved highly effective during the pandemic.”

- “The organization that I work for has a solid plan in terms of disaster and pandemic management. This institution has done an excellent job with the COVID-19 pandemic.”

On the other hand, more than 30 respondents noted that they did not know (or were unsure) what their organizations were doing in this area, or that their organizations had not taken action.

We also received 220 responses to our question asking about strategies that organizations are using to address the migration of traditionally inpatient procedures (for example, total joints, spine, and cardiac procedures) from the hospital to ambulatory care settings.

Most respondents noted that they did not know, were unsure, or did not anticipate a large impact, or they said their organizations had not taken any action.

Some organizations have built their own ambulatory surgery center (ASC), recruited physicians, and added more outpatient ORs, respondents said. Other comments included:

- “We have converted about 50% of our volume of total joints (hips, knees, and shoulders) to outpatient status by convening a multidisciplinary total joint team that reworked protocols, orders, and care plans to accommodate the change.”

- “Increasing education and setting the appropriate expectations with the patients and families. We also set up an after-hours clinic to prevent total joint patients from returning to the emergency department, and we have an orthopedic physician assistant to take call when patients and families have questions they need answered.”

COVID-19 has had a serious impact on staffing and volume in the OR. Just how long it will take to reverse the pandemic’s negative effects remains to be seen, especially with some facilities once again postponing elective procedures. OR leaders will need to call on all their leadership expertise to meet the ongoing challenges.

Business manager profile

The percentage of respondents with a business manager position was essentially unchanged at 38%, compared to 36% last year.

This year saw significant changes in business managers’ income.

- In all, 40% of business managers earn more than $100,000 annually, up from 26% last year and 27% in 2019.

- Annual salaries of $90,000 to more than $100,000 a year were reported for more than half (52%) of business managers, compared with 35% in 2020 and 40% in 2019.

- About one-fourth (26%) of OR leaders require business managers to have a clinical background, comparable to the 29% reported the past 2 years.

- For the first time in 10 years, a bachelor’s degree was more commonly required than a master’s degree, but only by two percentage points (48% vs 46%).

- The number of direct reports for business managers was up slightly, with 29% having 5 to 9 and 22% having 10 or more, compared to 37% and 11%, respectively, last year. Only 12% have no direct reports.

- The top three areas of responsibility for business managers are financial analysis and reporting (84%), annual budget (83%), and purchasing OR supplies and equipment (72%).

- Interesting shifts in responsibilities include increases in value analysis and product selection process (61% this year vs 48% in 2020) and strategic planning (58% this year vs 43% in 2020), and a decrease in those with billing and reimbursement responsibilities (58% vs 70% in 2020).

Survey: Dips in job satisfaction, engagement may relate to pandemic

Over the past year, job satisfaction of OR leaders as well as staff and physician engagement have all eroded, according to the 2021 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey. Although more than two-thirds (67%) of respondents rate their current jobs or positions favorably, that is down from the 77% seen in 2020 and 70% in 2019. Only 18% of respondents say that they are “completely satisfied,” compared to nearly a third last year.

OR leaders report a favorable level of engagement for slightly more than half of both staff (53%) and physicians (55%), down from the 70% and 65%, respectively, seen in 2020. The continuing pandemic may have played a role in these results, although the percentages are only slightly higher than those from 2019 (51% of staff and 49% of physicians). It may be that an engagement surge caused by the need to quickly respond to a crisis has faded.

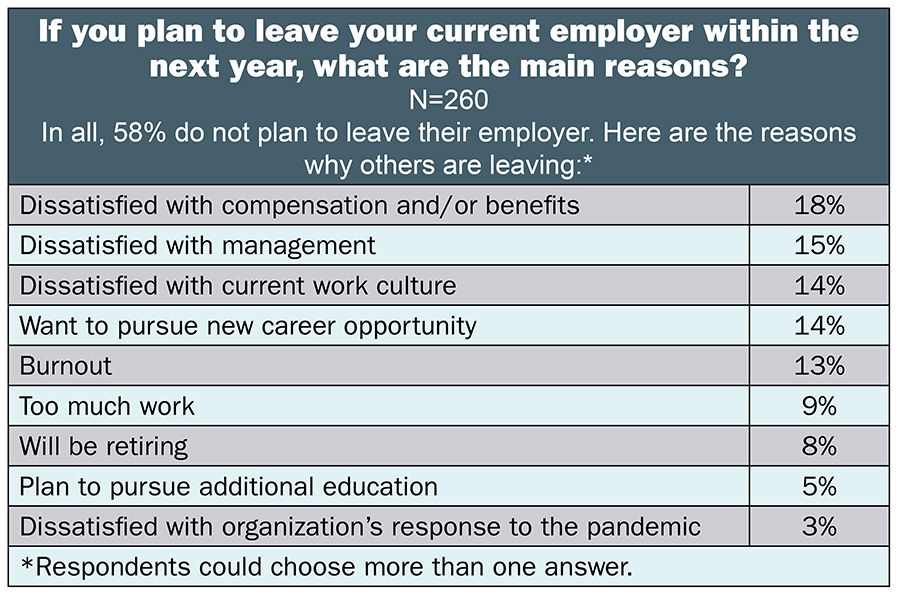

Although most respondents (83%) report that the COVID-19 pandemic has not changed their career plans, 15% plan to shift to a different work setting or leave the profession entirely. More than half (58%) of respondents say they do not plan to leave their employers in the next year, but that leaves a potentially large proportion who might do so, which could create significant turmoil for hospital administrators. The results are similar to those of a February 2021 survey by the American Organization for Nursing Leadership, which found that 10% of nurse leaders were considering leaving or planned to leave nursing.

Despite the added stress and responsibility related to the pandemic, OR leaders’ salaries and compensation remain comparable to 2020 levels, with 31% earning salaries of $150,000 or more, essentially unchanged from the 30% in 2020, and 15% reporting total compensation of $200,000 or more, similar to 17% last year.

Other highlights from the 2021 survey include:

- The average number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees that OR leaders supervise is 119, compared to 146 in 2020 and 139 in 2019.

- Nearly two-thirds (62% vs 63% in 2020) of respondents manage an annual operating budget in the $2.5 million to $49.9 million range, but overall, budget responsibilities increased slightly from last year.

- Staffing is OR leaders’ top concern when it comes to the future of perioperative nursing.

Respondents’ salaries and compensation earnings are stable, with 79% earning an annual salary of $100,000 or more this year, comparable to 78% in 2020. Only 4% (vs 2% in 2020) earn less than $60,000.

As expected, earnings vary by title, with 75% of administrators and administrative directors earning $150,000 or more, compared to 35% of directors and assistant directors, and 8% of nurse managers. After that option, most of those with the title of director or assistant director reported earning $100,000 to $119,999 (23%) or $120,000 to $149,999 (27%). Most nurse managers selected the $100,000 to $119,999 (33%) or $120,000 to $149,999 (25%) options for their salary ranges.

Salary also varied by region, with respondents in the Midwest and South most commonly reporting an annual salary between $100,000 and $119,999 (31% and 29%, respectively) and those in the West and Northeast most commonly reporting $150,000 or more (45% and 32%, respectively).

Annual salaries were relatively similar between those working in teaching and community hospitals, with 80% of community-based OR leaders earning $100,000 or more, compared to 78% of those in teaching facilities. However, 35% of those in teaching hospitals earn more than $150,000, compared to 27% in community hospitals.

As in 2020, the most frequently reported total compensation range was $120,000 to $149,999 (25% for both years). Only 7% (unchanged from 2020) received less than $80,000 in total compensation.

The most common total compensation ranges based on role were $200,000 or more for vice presidents or chief nurse executives (71%) and administrators or administrative directors (42%), $150,000 to $174,999 for directors or assistant directors (27%), and $120,000 to $149,999 for nurse managers (34%).

Regional patterns for compensation differed from those for salary. Respondents in the Midwest (30%), West (29%), and South (24%) most commonly reported $120,000 to $149,999 as the range of their total compensation. For those in the Northeast, the most common range was slightly lower at $100,000 to $119,999 (23%).

OR leaders in teaching hospitals reported higher total compensation than their counterparts in community hospitals. More than half (54%) of those at teaching hospitals earn $150,000 a year or more, compared to 47% for those based in the community setting. In addition, nearly one-fourth (23%) of those in teaching hospitals earn $200,000 or more, compared with 11% of those in community facilities.

Nearly two-thirds (63%) of respondents had received a raise in the past 12 months, down from 68% in 2020 and 70% in 2019. The average raise was 3.3%, higher than the 2020 consumer price index of 1.4%.

When choosing from the survey’s options for titles, most respondents selected nurse manager (43%), followed by director/assistant director (40%), administrator/administrative director (13%), and vice president/chief nurse executive (4%).

OR leaders supervise an average of 97 clinical FTE positions, up from 83 last year, and 22 nonclinical FTE positions, down from 63. In 2019, the numbers were 102 and 42, respectively. The large change in nonclinical positions may be due to layoffs, or it could simply be an anomaly. The oversee increased from 2020, with 25% managing six to 10 rooms (vs 21% in 2020) and 21% overseeing 11 to 15 rooms (vs 15% in 2020). Those who manage one to five ORs dropped from 41% last year to 22% this year.

Budget responsibilities increased slightly from last year, with 24% now responsible for an operating budget of $50 million or more, compared to 17% last year; 39% manage a budget of $10 million to $49.9 million, compared to 23% in 2020.

A similar trend occurred with the capital budget. More than a third (36%) of respondents oversee a budget of $2 million or more, up from 24% in 2020, and only 29% manage a budget of $499,999 or less, down from 49% last year.

Compared to last year, fewer leaders are satisfied with their current jobs and total compensation. Less than half (45%) of respondents rated total compensation favorably, compared to 60% in 2020 and 51% in 2019. However, satisfaction in most other areas was comparable to last year, with high favorability ratings for patient satisfaction with OR services (81%), support provided by the respondent’s boss (70%), benefits (67%), and top leadership (57%).

Declining satisfaction may have contributed to the 42% who appear to be open to leaving their employers in the next year. The most common reasons given for leaving were dissatisfaction with compensation and/or benefits (18%), dissatisfaction with management (15%), dissatisfaction with current work culture (14%), and desire to pursue new career opportunities (14%). Interestingly, although 15% were dissatisfied with management, only 3% were dissatisfied with their organization’s response to the pandemic.

Benefits often play a key role in employee retention, so we asked respondents to select from a list of benefits they would like to have if they did not already have them. The top three responses confirm that money talks: bonus (48%), profit sharing (22%), and pension plan (20%). However, nearly one-fourth (24%) did not choose any of the benefit options on the list.

Overall demographics are listed in the infographic. The average age of the OR leaders who responded to the survey is 53, higher than the 44 years (from 2018) cited in The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 Report, released in May 2020.

OR leaders appear to be a less diverse group when compared to the general nursing profession. Most respondents (83%) chose white as their race or ethnicity, followed by Asian (4%), African American/Black (3%), Hispanic/Latinx (3%), American Indian/Alaska Native (1%), and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (less than 0.5%). The categories used in the Future of Nursing Report differ slightly, but the percentages are worth noting: 69% for white, 12% for African American/Black, 9% for Asian, and 7% for Hispanic.

A master’s remains the highest degree held by most OR leaders (48% vs 41% in 2020), with most of those being in nursing (31%). More than a third (35%) report a baccalaureate as their highest level of education, down from 45% in 2020. Only 6% listed a doctorate as their highest degree.

More respondents (60%) work in a community hospital than in a teaching hospital (31%). Respondents were fairly evenly divided among the South (30%), Midwest (29%), West (21%), and Northeast (20%).

More than half (54%) of OR leaders have more than 10 years of experience as a perioperative manager, down from 66% in 2020, and 15% have 26 or more years of experience, down from 23% last year. They work an average of 51 hours each week.

The survey asked: What is your biggest concern about the future of perioperative nursing? Of the 220 OR leaders who responded to that question, staffing was by far the top concern, with nearly every person listing some aspect related to it. “Lack of trained and committed nurses!” is a representative comment.

Staffing concerns include the lack of opportunities to gain perioperative experience in nursing school, nurses not having the expertise needed as technology increases, an aging workforce, the inability to retain nurses because of burnout, the inability to offer sufficient wages (which also may result in nurses going to agencies to work), and nurses not wanting to take call. Another concern is the inability to fill leadership positions that will be open as a result of retirement.

Sample comments include:

- “Lack of perioperative exposure in nursing school, which has decreased interest and impacts the pipeline.”

- “Nursing schools emphasize ICU nursing experience for new grads as a first step for nurse practitioner school and career advancement. Nursing students do not know about perioperative nursing careers and have little to no opportunities as a student in their rotations.”

- “The Millennial generation does not have the loyalty of previous generations. Trying to develop a team that has experience is going to be a challenge. No one wants to work weekends, holidays, or off-shifts.”

- “Surgical technicians leaving for larger institutions, more pay, more interesting cases, bonuses offered, etc.”

- “Most new grads want to get trained, and then after a year or so, they decide their life goals are to travel (travel nursing) to earn money for a home and travel before settling down. This leaves us with many new (novice) nurses in the OR who do not have enough expertise to mentor new nurses, which suggests a probable future impact on patient safety and outcomes.”

Other areas of concern are reimbursement, costs, quality, lack of supplies, and higher workloads. Comments related to some of these areas include:

- “The continued move toward outpatient services as well as the continued decline in reimbursement for services will mean a significant decline in the quality of nursing care provided.”

- “Fewer generalists and more specialized teams reduce the ability to plug urgent cases into open rooms.”

- “Perioperative nurses have to work smart, and they need to get additional skills in digital technology.”

- “There is constant pressure on staff for faster turnovers and increasing documentation. Patient safety.”

- “Medicare/Medicaid cuts are forcing inpatient procedures into the outpatient world.”

- “Having quality staff, communication, a culture of respect, and teamwork in the OR is important.”

- “The complexity of cases and equipment is increasing everywhere. Outpatient services and sites are doing many more complex cases. IT systems cannot keep up with the integration needs and/or IT support and technology required.”

- “Senior administration does not understand the perioperative department other than as the money department, so the expectation is that surgery ‘just makes it happen.’ This mentality is exhausting and causes burnout in the department.”

- “Access to capital; the cost of business and new technology is so high, but we need [the capital] to remain competitive.”

Much uncertainty surrounds the future of perioperative nursing as healthcare systems continue to cope with the effects of the pandemic. As one respondent notes, “How will we care for patients in the future? Will there be enough nurses, and if not, what changes will we need to make to care for the community?” OR leaders will need every ounce of their vast expertise to lead their teams into the future.

About the survey

Data for the OR Manager Salary/Career Survey were collected from March 22 to May 14, 2021. The survey list comprised OR directors, managers, or similar positions within hospital ORs. The survey was closed with 342 usable responses. The margin of error is ±5 percentage points at the 95% confidence level. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Survey: ASC leaders continue to feel pandemic pain

Consistency is the word that comes to mind when reviewing results from the 2021 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, leaders in ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) reported that salary, satisfaction, and the number of employees supervised were comparable to metrics reported in 2020. The good news is that most respondents (84%) say the COVID-19 pandemic has not changed their career plans.

Slight movement did occur in a few areas. Total annual compensation fell slightly: 40% of respondents earn $120,000 or more, down from 53% in 2020, but consistent with a pre-pandemic level of 42% in 2019. In addition, the percentage of those responsible for an annual operating budget of $5 million or more increased from 19% in 2020 to 25% this year; that compares to 16% in 2019.

Other results from the survey include:

- Only 6% of respondents plan to leave the profession as a result of the pandemic, but an additional 10%plan to change to a different work setting. That is similar to the 10% of nurse leaders who indicated they were considering leaving or planned to leave nursing, as reported in a February 2021 survey by the American Organization for Nursing Leadership. Any migration, however, could add up to a significant number of managers exiting at a time when finding successors is likely to be particularly difficult.

- In all, 59% of ASC leaders plan to retire in 2030 or later, although nearly 1 in 5 (19%) plan to exit the workplace by 2025.

- The average raise was 3.5% (vs 3% in 2020 and 3.2% in 2019); the consumer price index for 2020 was 1.4%.

- Most respondents (31%) have 1 to 5 years of experience as a perioperative manager.

Here are some additional findings.

More than half (51%) of respondents earn an average annual salary of $100,000 or more, similar to last year’s 59%. The most common salary range was $100,000 to $119,999 (27%). Only 6% earn $150,000 or more (vs 11% in 2020), and only 3% earn less than $60,000 (vs 2% in 2020).

Not surprisingly, earnings vary by title. For example, the most common salary range for leaders with the titles of administrator/administrative director or director/assistant director was $100,000 to $119,999, but for nurse managers, it was $90,000 to $99,999. Interestingly, the most common range for three geographic regions—Northeast, Midwest, and West—was $100,000 to $119,999; for the South it was $120,000 to $149,999.

The two most common ranges for total annual compensation were $100,000 to $119,999 (25%) and $120,000 to $149,999 (24%). Only 3% of ASC administrators earn $200,000 or more (vs 7% in 2020), and only 12% earn less than $80,000 (vs 11% in 2020).

The most common total compensation range for those who serve as directors/assistant directors was $120,000 to $149,999, and for administrators/ administrative directors and nurse managers, it was $100,000 to $119,999. Respondents in the Northeast, South, and West most commonly reported total compensation in the range of $120,000 to $149,999, with $100,000 to $119,999 the most common range for those in the Midwest.

ASC leaders supervise an average of 32 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, 26 of whom have clinical roles and 6 of whom have nonclinical roles. The average is lower than the 35 FTEs noted in 2020, but the same as what was reported in 2019.

More than half (52%) of respondents said they did not know their ASC’s annual operating budget, up from 37% in 2020 and 2019. One-fourth (vs 19% in 2020) oversee a budget of $5 million or more. Only 2% manage a budget of $15 million or more. In the past 12 months, 28% saw their operating budget increase, whereas it decreased for 19% and stayed the same for 53%.

Most respondents (79%) oversee one to five ORs (vs 81% in 2020 and 77% in 2019), with most responsible for two (29%), three (20%), or four (18%). Only 6% have 10 or more ORs under their management, the same as last year.

Overall, ASC leaders’ satisfaction ratings are comparable to those from last year. The exception is physician engagement level, which received a favorable rating from 73% of respondents, up from 59% in 2020. It will be interesting to see if the improvement is sustained next year.

As in previous surveys, respondents gave patient satisfaction with OR services their highest favorable rating (96%), far above the next highest—78% said they were satisfied with their own job or position (vs 76% in 2020). The only other item receiving more than 70% was staff engagement (76% vs 79% in 2020).

More than two-thirds (69%) of respondents plan to stay with their employers—at least for the next year. For those planning to leave, the top three reasons were burnout (14%), dissatisfaction with compensation and/or benefits (12%), and too much work (also 12%).

Benefits can motivate managers to stay on the job, so we asked respondents to select from a list of benefits they would like to have if they didn’t already have them. The top four responses were: bonus (35%), profit sharing (29%), tuition/education reimbursement (27%), and pension plan (23%). However, nearly one-fourth (24%) did not choose any on the list.

Overall demographics are listed in the infographic. The average age of the respondents was 51 years, higher than the 44 years cited in The Future of Nursing 2020-2030 Report, released in May 2020.

ASC leaders spend an average of 47 hours on the job each week, with the number of hours ranging from 30 to 80. One-third of respondents have 5 years or less of experience (vs 20% in 2020), and 21% have more than 20 years of experience (down from 34% in 2020).

ASC leaders appear to be a less diverse group than the general nursing profession. Most respondents (88%) chose white as their race or ethnicity, followed by Hispanic/Latinx (4%), and Asian (2%); 5% preferred not to answer. None chose African American/Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander. The categories used in the Future of Nursing Report differ slightly, but it is interesting to note the percentages: 69% for white, 12% for African American/Black, 9% for Asian, and 7% for Hispanic.

Most ASC leaders (42%) report a baccalaureate degree in nursing as their highest level of education, and 20% (vs 29% in 2020) hold a master’s degree, although only half of those are in nursing. Of the title options provided in the survey, the top three chosen were administrator/administrative director (35%), followed by director/ assistant director (33%) and nurse manager (29%).

A total of 33% respondents live in the South, 29% live in the Midwest, 21% in the Northeast, and 18% in the West.

In all, 106 respondents answered the question: “What is your biggest concern about the future of perioperative nursing?” Almost every comment related fully or partly to staffing. Concerns included finding and retaining qualified staff in an era when, as one ASC leader noted, “Nurses are continually asked to do more.” Burnout, generational differences, not being able to pay staff sufficient wages, replacing aging nurses, and schools not preparing perioperative nurses were cited more than once.

Sample comments include:

- “[There is] a lack of experienced RNs, techs, managers, supervisors, and administrators. No one seems to want to move up into the leadership roles.”

- “[There is] reduced passion on the part of the current generation for dedicating themselves to perioperative nursing.”

- “Young nurses in my experience are not committed to places or coworkers. They hop from job to job, and it will be hard to maintain integrity of staffing when current RNs retire.”

- “Surgical techs are very difficult to find; sterilization staff is difficult to find and keep.”

- “There are not a large number of nursing programs that include perioperative nursing in the curriculum.”

- “[There is] brain drain as experienced teammates retire before new teammates have gained experience.”

- “The challenge is finding truly experienced outpatient perioperative nurses. It requires a high level of autonomy to thrive in ASCs and is challenging for many who are reliant on the support from the larger healthcare settings.”

Some mentioned that they are trying to address staffing issues. “We are working to grow our own perioperative staff in our center, hiring new grads and somewhat inexperienced RNs. We are crafting our education to meet our needs and the staffs’ needs,” says one respondent.

Other concerns include decreased reimbursement, surgeon issues, and supply chain issues, as reflected in these sample comments:

- “I see fast-tracking being the wave of the future, with surgeries taking less time and patients being rushed through the process.”

- “A secondary challenge is around the decreasing reimbursement to ASCs, as it is almost half of what the hospital receives for the same procedure. The disparity in the reimbursement structure is something that truly needs to be addressed as many ASCs are having to become fully contracted centers and the out-of-network cushion has all but disappeared.”

- “I feel that the general public is not educated enough about their healthcare plans to understand how outpatient surgery at a surgery center can save them a significant amount of money. If we can attempt to educate the general population on the financial implications and savings, we may see a greater migration to outpatient venues.”

The post-pandemic road may be a bumpy one, but ASC leaders stand ready to lead. As one respondent notes: “I am excited for the future of perioperative nursing as cases transition from hospitals to ASCs.” Another adds: “We who have been in ASC leadership for many years have worked hard to share our victories in delivering safe patient care. I want to be sure as I leave my career, in about 2 to 3 years, that our ASC perioperative quality and outcomes remain excellent.”

Retaining nurses in a

post-pandemic era

The ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic run deep in the nursing profession. As one respondent to the 2021 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey noted: “[The pandemic has] caused healthcare workers to rethink the reason they went into this profession. Also, the fact that we could die doing our jobs.”

Part of that rethinking by nurses is whether to stay in their jobs or even the profession, for both professional and personal reasons. “Some nurses who have been away from family for over a year because of social distancing requirements] are deciding they don’t want to do that anymore, so they are moving closer to their grandkids,” says Michelle Sanchez-Bickley, MS, SPHR, SHRMSCP, chief human resource officer of Renown Health in Reno, Nevada.

In an early 2021 survey of more than 22,000 US nurses by the American Nurses Foundation (ANF), 18% of respondents planned to leave their positions in the next 6 months, and 4% planned to leave the profession. With OR leaders already struggling to find qualified perioperative nurses, retention is more important than ever.

“Leadership is key to any retention strategy,” says Ila Minnick, MS, BSN, RN, president of Interim Leadership Associates in Rockford, Illinois. “We have nurses who are totally worn out [as a result of the pandemic], so we need to focus on nurse well-being and helping nurses through burnout.” In addition, some nurses who have had COVID-19 may be suffering from its long-term effects.

Michelle Sanchez-Bickley, MS, SPHR, SHRM-SCP

Michelle Sanchez-Bickley, MS, SPHR, SHRM-SCP

Ila Minnick, MS, BSN, RN

Ila Minnick, MS, BSN, RN

In the ANF survey, 21% of nurses were undecided about whether they would leave their positions, and 11% were undecided about whether they would leave nursing. The 2020 National Nursing Workforce study, which spanned February to June, found that more than one-fifth of nurses plan to retire over the next 5 years. That adds to the potential number of nurses who could leave, creating not only a patient safety issue, but a financial one as well. According to the 2021 National Health Care Retention and RN Staffing Report, the average cost of turnover for a hospital-based RN was $44,400 in 2020; that’s likely higher for a perioperative nurse.

The same report found that the average staff RN turnover rate was 18.7%, up by 2.8% from 2019, and vacancy rates were about 9.9%, compared to 8.9% the previous year.

Whether or not the pandemic prompts more nurses to leave, turnover will remain a concern for OR leaders. A pre-pandemic study of more than 207,000 nurses by Koehler and Olds found that 21% of nurses intended to leave their positions in the next year, in line with previous research.

Thomas Koehler, BSN, RN, CNOR

Thomas Koehler, BSN, RN, CNOR

The pandemic has hit younger nurses harder than their older counterparts. The ANF survey found that 81% of nurses aged 34 years and younger reported feeling exhausted in the past 14 days, compared to 59% of those 35 years and older.

Part of the stress likely comes from the unique situation faced by new graduates—who are usually from younger generations—as a result of the pandemic. These nurses are coming to the workplace less prepared because of reduced clinical time. Leaders need to realize that although simulation helped mitigate some of that loss, new graduates will still require extra time for orientation, especially given that most will arrive with little OR experience.

“We are expanding the orientation time for new graduates, giving them more time in the classroom and in the OR,” says Michelle Hopson, MSN, RN, NPD-BC, director of clinical professional development at Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital in Baltimore. “We want them to feel supported and not overwhelmed, so that they’re more likely to stay.”

Even before the pandemic, however, generational differences played a role in retention. In the Koehler and Olds study, intention to leave varied by generation, with Millennials more likely to respond that they intended to leave than Generation Xers and Baby Boomers.

Those in the Silent Generation were most likely to intend to leave, probably because of retirement. Millennial and Generation X nurses more commonly cited family obligations as a reason for leaving, but Generation Z nurses ranked pursuing a different nursing specialty higher than these obligations.

“Leaders should be aware that the needs of different generations might vary,” says study coauthor Thomas Koehler, BSN, RN, CNOR, a perioperative nurse at John Muir Health-Walnut Creek Medical Center in Walnut Creek, California. “If OR managers can recognize those generational differences and can work with them to retain nurses, it will keep their unit, their team, and their employees closer together.”

One difference is that younger generations are more mobile than older nurses. “You spend a lot of time orienting people for perioperative nursing, and then they leave in 1 to 2 years,” Minnick says. Nurse residency programs can help lessen turnover, but leaders still must meet the unique needs of younger nurses. For example, younger nurses will not sacrifice work-life balance, so mandatory overtime will simply push nurses away.

Sanchez-Bickley agrees: “For the first time, there are five generations in the workplace, and they want and need different things. We try to offer different benefits at different points in someone’s career life cycle.” For instance, help with student loans may be more important to younger nurses than 401K contributions. Older nurses will appreciate knowing how they can make “catch up” contributions to their 401K plans. Renown Health also offers child care benefits and onsite childcare from infancy up to 5 years, which appeals to younger nurses, and it has reduced the amount of time needed for younger nurses to reach higher levels of pay ranges.

Because younger generations want to advance quickly, Renown Health opened its clinical ladder program to new graduates instead of making them wait a year or two. “We’ve found that new grads who participate are more likely to be retained and continue on the ladder,” Sanchez-Bickley says. “It has been a popular program.”

Koehler says research is lacking on which retention strategies work for each generation, but criteria such as pay, staffing, and workload are important to all generations. In fact, workload and staffing were among the most common reasons for intending to leave cited by all generations.

Job embeddedness (JE), a concept developed in the organizational psychology field, can be a helpful way to frame retention. “Job embeddedness is a model that looks more at why people stay in their positions rather than focusing on why they leave. It [creates] a positive perspective when looking at retention,” says Hopson. She was the principal investigator for a mixed-methods study of JE, which has been linked to retention and higher job satisfaction.

“Job embeddedness can be conceptualized as a three by two matrix,” says O. Erin Reitz, PhD, MBA, NEA-BC, associate professor at the Mennonite College of Nursing at Illinois State University in Normal. “It looks at fit, connections, and sacrifice, not only between a person and their organization, but also between a person and their community”. A study by Reitz and colleagues found that JE is a good predictor for a nurse’s intent to stay, and Hopson’s study found that being older, having ties to the community, and having peer relationships were most indicative of JE.

Leaders can use the six aspects of JE to create a retention plan. “Strategies for job embeddedness have to be based on the unique aspects and characteristics of the organization and the community,” Reitz says. For instance, some nurses may prefer to work for a religious-based organization, whereas others prefer a secular one. And some might prefer a smaller town rather than a big city.

Leaders also should consider the strengths and weaknesses of the organization and community. For example, Reitz lives in an area with three schools of nursing, so the links created by students doing clinical rotations in the organization and the fact that most students live in the community are strengths.

As part of her study, Hopson used focus groups and an online survey to collect information about the degree of JE among nurses. OR leaders could use the questions in staff interviews or as a survey. Leaders also could use the survey to assess individual factors such as the work environment.

Links are particularly key when developing a JE-based retention plan. “The more links people have to both the organization and community, the more embedded they are,” Hopson says. She notes that many participants in her study said they would not want to leave the organization because it would mean leaving people they enjoy working with, which reinforces the importance of teams. “Build in opportunities for staff to connect with each other both at work and outside of work,” she says.

“Pay and benefits are important, but as I talk with staff, that isn’t what they bring up first,” Minnick says. “They want a good team to work with. When you work with a good team, there is a lot of satisfaction.” She adds that having a leader (including a charge nurse) who knows how to coordinate care and show appreciation for everyone will help retain staff, which means leadership development is integral for retention.

A common recruitment strategy to avoid is a relocation bonus, which does not promote retention, Reitz says. A relocation bonus may draw a nurse from an urban to a rural area, for example, but in too many cases, nurses return to the original area once their 1- to 2-year commitment ends.

“What’s more effective is to grow your own, focusing on those already embedded in the community,” Reitz says, adding that an educational incentive for a nurse to obtain a BSN or higher education at a local college builds community connection, making it more likely a nurse will stay in the area.

JE requires what Sanchez-Bickley refers to as a “wrap-around” approach that includes a positive job environment and community connections. For example, Renown Health gives staff time off to volunteer in the community and offers classes on how to buy a home. “It’s important for nurses to feel supported,” she says.

Of course, JE is not a panacea for turnover. A study by Marsai and colleagues of more than 300 nurses found that those with low organizational trust but high JE engaged in more workplace deviance than those with low organizational trust and low job JE.

Hopson notes that JE could unintentionally result in nurses staying when they should not, for instance, in the case of lateral violence. In addition, nurses may feel stuck, rather than embedded, because they do not have enough options for growth. To address this, Marsai and colleagues suggest letting employees know about other job opportunities and providing more generalizable skills training.

“There’s no one recipe or template, no magic bullet for nurse retention,” Reitz says. Strategies must be tailored to each organization. “What might work for one might not work for another, depending on the community and the culture of the workforce.”

O. Erin Reitz, PhD, MBA, NEA-BC

O. Erin Reitz, PhD, MBA, NEA-BC

Donna Doyle, DNP, RN, CNOR, NE-BC

Donna Doyle, DNP, RN, CNOR, NE-BC

Kate Ulrich, MS, BSN, RN, NEA-BC

Kate Ulrich, MS, BSN, RN, NEA-BC

Even as vaccination rates rise, COVID-19 continues its grip on the healthcare system and are feeling the consequences, including staffing challenges that have prompted a renewed focus on retention. Scars left by the pandemic will complicate retention efforts.

“The pandemic has made things much worse, not only for the nursing shortage but for nurses working in the profession who never had any plans to leave or retire,” says Donna Doyle, DNP, RN, CNOR, NE-BC, perioperative consultant, DJD Consulting Services in Columbus, Ohio. Nurses have experienced personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages, longer work hours, post-traumatic stress disorder, unsafe work environments, and an inability to provide the care they wanted to deliver. Many were furloughed or lost their jobs and did not return when the pandemic eased.

“There has been a loss of trust in the organization they work for and a loss of trust at the state and federal levels,” Doyle says. “This has contributed to the fact that nurses are at the precipice of deciding whether they want to continue to be nurses.”

How can leaders rebuild trust? What else can they do to retain staff? OR Manager provides strategies in several key areas, including work environment, well-being, recruiting and onboarding, and career development.

“One of the biggest ways to retain nurses and help re-establish trust is to make sure you have a safe work environment,” says Doyle. That includes having sufficient PPE, making sure there are mechanical aids for lifting and moving patients, and eliminating smoke in the OR. “Nurses need to feel that the organization is looking out for them and not just looking out for the profit margin,” she says.

Building relationships through communication fosters a healthy work environment. “You have to have an open dialogue between the organization and the staff,” Doyle says, adding that small group and town hall meetings with a Q&A format promote dialogue.

OR leaders should be honest about what can and cannot be done to address issues and about what the organization is doing. “Be transparent,” says Kate Ulrich, MS, BSN, RN, NEA-BC, assistant vice president of nursing, perioperative services at Duke Health in Durham, North Carolina. “It’s important to keep people informed.”

It is also important to listen. “That’s something the pandemic taught us—to listen to team members even more than we did before,” Ulrich says. “On a daily basis, the teams are the ones who are doing the work. We need to listen to be sure they have what they need to take care of our patients.” The “1 Duke Periop” program, which encourages multidisciplinary teamwork, has helped promote staff input, foster collaboration, and implement change where needed.

“You need to really invest time into building a relationship with your team and getting to know them as individuals,” says Michele Brunges, MSN, RN, CNOR, CHSE, director of perioperative services at UF Health Shands in Gainesville, Florida. “The only way you can meet their needs is to understand where they are coming from and what’s important to them.” The organization recently sent leaders to a course on stay interviews (one-on-one interviews that help leaders identify factors contributing to the employee’s retention), which they plan to do quarterly and as part of monthly meetings during orientation, which lasts 6 months (sidebar, “Stay interviews”).

Nurse leaders also should build a strong relationship with HR staff because they can help with tracking turnover and identifying why people are leaving—and staying. HR leaders can calculate retention rates based on predetermined criteria that should remain consistent so trends can be identified. Ultimately, a good work environment is what is going to retain nurses, says Michelle Sanchez-Bickley, MS, SPHR, SHRM-SCP, chief human resource officer for Renown Health in Reno, Nevada. “You have to have good compensation and benefits, but at the end of the day, provided those are where they need to be, it’s about the team, it’s about their leader, and it’s about them having meaningful work.”

“There absolutely needs to be a focus on well-being,” says Ulrich. “We know that many nurses are feeling burned out.” In an early 2021 survey by the American Nurses Foundation (ANF), the top reason nurses gave for wanting to leave their positions in the next 6 months was that work was negatively affecting their health/well-being (insufficient staffing came in close second). Ulrich encourages OR leaders to check in with staff on a regular basis and remove barriers that can impede a nurse’s work.

In addition to an employee assistant program, Duke Health’s chaplain service provides “Tea for the Soul.” Chaplains share different types of tea as they meet with small groups of team members, providing the opportunity to share feelings. Another program is “Caring for Each Other.” Team members who feel the need to talk to someone after a traumatic event can page a multidisciplinary team that includes organizational leaders, a member of chaplain services, and staff from the employee assistance program. “It helps us hone in on what the team member needs at that moment,” Ulrich says.

Doyle says one way to improve wellbeing is to provide a respite room or even a quiet corner that has soft music, aromatherapy, and a yoga mat. “It’s an area where nurses can go when they’re feeling overwhelmed,” she says. “They can get away for even 10 minutes and recoup.”

When Doyle was senior advisor of surgical services at Grant Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio, the facility used Schwartz Rounds, which allow staff to decompress and talk about difficult cases, patients, and families on an emotional level. “This is not just a taskdriven profession; it can be emotionally exhausting and trying,” she says. Rounds were held on units and kept to 30 minutes to facilitate attendance.

Finally, well-being can be enhanced through positive interactions between staff and leaders, which benefits staff. For example, a 2021 study by Sexton and colleagues found that Positive Leadership WalkRounds improved staff wellbeing, with less emotional exhaustion. During rounds, leaders asked staff to share three things that are going well in the work setting, one thing that could be better, and if there is anyone who should be recognized. The rounds improved the culture of safety because staff were more eager to engage in quality improvement activities.

It is not surprising that recognition was part of the rounds, given that employees often state they would like greater acknowledgment of what they do. Brunges says that at UF Health Shands, a perioperative services team meets monthly to create ways to recognize their peers. In addition, the organization has its own recognition program that includes coffee cards, ice cream, T-shirts, and employee of the month.

“For some people, these types of rewards are very important,” Brunges says. She adds, however, that it is important to individualize rewards. “Flexible scheduling meets a lot of people’s needs, but others may have different things they appreciate.”

Retention begins with recruiting the right staff. OR leaders should not rush the process in an effort to plug a vacancy, but rather focus on how a nurse would fit within the organization and team. “For a candidate to love an organization, they have to love their leader, so the more leaders can be involved in the recruitment process, the better,” says Sanchez-Bickley.

Organizations may want to start recruiting even before nurses graduate. Ulrich says Duke Health partners with Duke University School of Nursing to offer an elective course on perioperative nursing. Duke perioperative educators teach the course, which is full every semester. “Nursing students are our future, so we need to expose them to the OR,” she says.

Tight staffing and education staff stretched too thin can tempt OR leaders into shortcutting onboarding, but Rose Sherman, EdD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN, warns that would be a mistake. “We know that many employees decide whether they’ll stay with employers during the onboarding experience,” says Sherman, adjunct professor at the Marian K. Shaughnessy Nurse Leadership Academy, Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, and author of The Nuts and Bolts of Nursing Leadership: Your Toolkit for Success and The Nurse Leader Coach: Become the Boss No One Wants to Leave. Using a checklist helps standardize onboarding and ensures that nurses both new to the OR and those with experience have a smooth transition.

Sherman recommends leaders be intentional about welcoming staff and showing them they are valued team members. Preceptors are key to this process, so leaders should choose them carefully and provide adequate training.

At UF Health Shands, new staff receive a welcome bag with a notebook, pen, and candy, and their photo is posted on a welcome board outside the OR. Before the pandemic, the leadership team had a luncheon with new employees each quarter. “We introduced ourselves and shared our experiences, and then staff introduced themselves and shared,” Brunges says, adding that they look forward to restarting the luncheons. Sharing often included fun personal information such as stories about pets and children. Regular check-ins with new nurses help to detect problems early. Sherman recommends meeting with new staff at the end of the first week, at 30 days, at 60 days, and mid-year. “Ask how things are progressing, and assess their satisfaction level,” she says.

Michele Brunges, MSN, RN, CNOR, CHSE

Michele Brunges, MSN, RN, CNOR, CHSE

Rose Sherman, EdD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN

Rose Sherman, EdD, RN, NEA-BC, FAAN

Sherman recommends starting professional development during onboarding. “Learn about each new staff member’s personal goals for their career, and begin the individual development plan,” she says. “Help new staff develop at least two to three personal development goals.” The goals should include actions and a timeline. Sherman adds that leaders should also have a list of professional growth opportunities for staff to “grow in place” in the OR.

Sanchez-Bickley agrees that leaders should know about available opportunities as well as who is thinking about retiring, moving, or advancing in the organization.

Ascension Saint Agnes Hospital in Baltimore has a nursing career coach. “She works with [nurses] to see if there are other areas where they can thrive so we are still retaining them at Ascension, but we are helping them grow as professionals,” says Michelle Hopson, MSN, RN, NPD-BC, director of clinical professional development. Nurses learn about the career coach in orientation, and the information is posted online.

Nurses can develop their careers by serving as preceptors and mentors. Doyle recommends a combination of traditional and reverse mentoring, where a less experienced nurse mentors a more experienced colleague in a specific area of expertise. “Different generations bring different skills,” she says.

Career development requires leaders to address performance issues. Not doing so is disruptive to other staff. Ila Minnick, MS, BSN, RN, president of Interim Leadership Associates in Rockford Illinois, suggests following the Studer Group’s recommendation to identify high, middle, and low performers. “You want to build and re-recruit [keep engaged] high performers, develop middle performers, and address low performers,” she says. “It only takes one person to impact your entire department.”

Retention depends on developing effective leaders, which Minnick says too often does not happen. “Everyone is so caught up in outcomes, patient satisfaction, and working within financial parameters that leadership development can be overlooked,” she says.

One of the biggest factors for retention is the work environment, so OR leaders should do all they can to ensure a work place where staff can thrive. A culture where appropriate staffing levels are maintained, relationships and well-being are fostered, and employees feel they can grow in their careers will go a long way toward retaining nurses. “Staff want to feel proud of the care that they’re giving. If they can deliver quality care, they will feel good about the organization and hopefully remain in their roles,” Minnick says.

“You have to focus on everybody,” Doyle adds. “Just because somebody has been there for 20 years doesn’t mean they’re going to be there for 21.”

American Nurses Foundation. Pulse on the Nation’s Nurses COVID-19 Survey Series: Year one COVID-19 impact assessment. 2021. https://www.nursingworld.org/practicepolicy/work-environment/healthsafety/disaster-preparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/year-one-covid-19-impact-assessment-survey/.

Clinton M, Knight T, Guest D E. Job embeddedness: A new attitudinal measure. Int J Selection and Assessment. 2012;20(1):111-117.

Gibbs Z. Support nurses with job embeddedness. Am Nurs J. 2021;16(7):40-43.

Hopson M, Petri L, Kufera J. A new perspective on nursing retention: Job embeddedness in acute care nurses. J Nurses Prof Dev. 2018;34(1):31-37.

Koehler T, Olds D. Generational differences in nurses’ intention to leave. West J Nurs Res. Published online March 20, 2021.

Lee T W, Burch T C, Mitchell T R. The story of why we stay: A review of job embeddedness. Ann Rev Org Psychol Organ Behav. 2014;1:199-216. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurevorgpsych-031413-091244.

Marsai S, Cox S S, Bennett R J. Job embeddedness: Is it always a good thing? J Managerial Psych. 2016;31(1):141-153.

NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc. 2021 National health care retention and RN staffing report. https://www.nsinursingsolutions.com/Documents/Library/NSI_National_Health_Care_Retention_Report.pdf.

Paul M. Umbrella summary: Job embeddedness. Quality Improvement Center for Workforce Development. April 22, 2020. https://www.qicwd.org/umbrella/job-embeddedness.

Pink D. When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing. New York: Riverhead Books. 2019.

Reitz O, Anderson M, Hill P D. Job embeddedness and nurse retention. Nurs Admin Q. 2010;34(3):190-200.

Sexton J B, Adair K C, Profit J, et al. Safety culture and workforce wellbeing associations with positive leadership walkrounds. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2021;47(7):403-411. Published online April 21, 2021.