Survey: Surgical volume returns for many ORs, but staff shortages remain

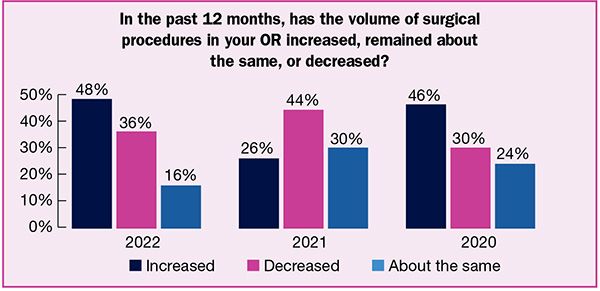

The good news from the 2022 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey is that in the wake of lessening disruption from COVID-19 throughout the country, surgical procedure volume has returned to many ORs, with nearly half of respondents (48%) reporting increased volume over the past year, double last year’s findings (26%).

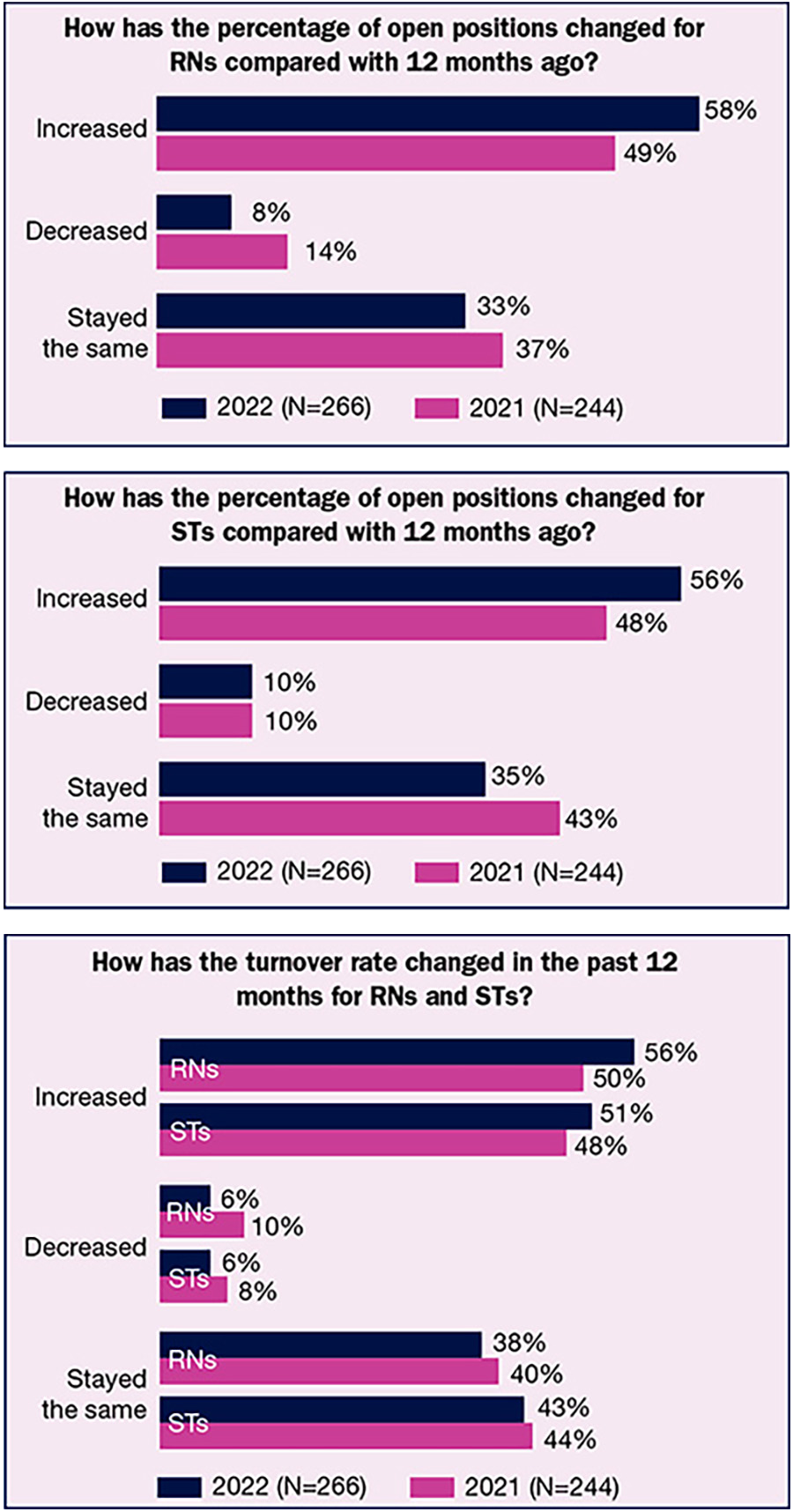

The good news is overshadowed by OR leaders struggling to find staff to meet the higher demand for surgery. Although the number of respondents who hired more direct care staff during the past year more than doubled, from 14% in 2021 to 32% this year, more than half report that the percentages of open full-time equivalent (FTE) positions for RNs and surgical technologists (STs) have increased in the past 12 months (58% and 56%, respectively).

Part of the staffing problem is turnover—more than half of respondents reported increased turnover in the past 12 months for both RNs (56%) and STs (51%). The staffing situation has led nearly half (47%) of OR leaders to increase agency and travel staff, compared to 35% last year. Although the pandemic’s impact on surgical volume may be easing, its grip on staffing remains strong: More than half (51%) of OR leaders lost staff because of the pandemic, up from 46% last year.

Other key findings from the survey include:

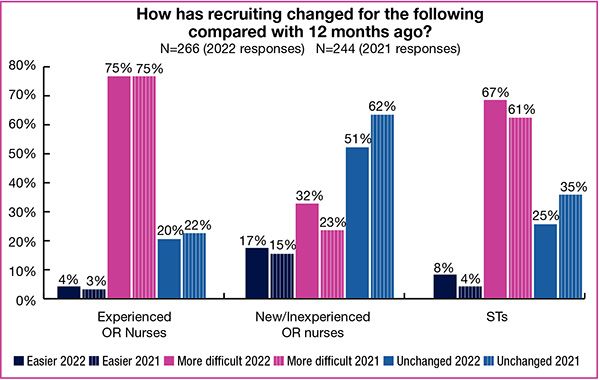

- The percentage of OR leaders who are finding it more difficult to recruit experienced RNs over the past year is 75%, unchanged from 2021, and the “difficult recruitment” percentages have increased for both STs and new or inexperienced OR RNs.

- Surgical volume has not increased for everyone: 16% reported decreased volume over the past year, indicating ongoing challenges. Over a third (36%) noted that volume had stayed the same.

This article outlines the survey’s findings related to staffing. (Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.) Read about results related to OR leaders’ compensation, scope of responsibility, and job satisfaction in the October issue of OR Manager.

Talk with any OR leader about their current challenges, and it is likely staffing will top the list. This year’s survey results related to turnover and open positions confirm the seriousness of this challenge.

A mere 6% of survey respondents said the turnover rate had decreased over the year for RNs and STs, with 38% reporting no change for RNs and 43% reporting no change for STs. Although the “no change” percentages are comparable to last year (40% and 44%, respectively), they fall far below the 61% reported for each role in 2020. The average turnover rate was 18% for both RNs and STs, but the ranges were wide (zero to 100% for RNs and zero to 80% for STs).

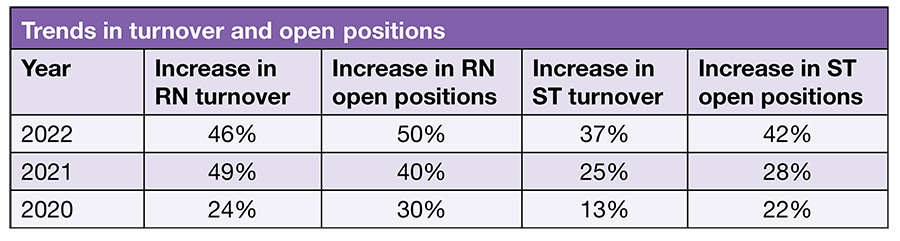

The high percentages for open FTE positions reflect increased turnover. Over half (56%) of OR leaders reported that open positions for STs had risen compared to 12 months ago, up from 48% in 2021. The percentage of RN open positions was also higher than last year: 58% vs 49%. Again, the comparison to 2020 increases is striking—33% for STs and 30% for RNs. Few respondents reported a decrease in open positions this year: 10% for STs and 8% for RNs.

Current open positions also tell the staffing tale, with 21% of respondents reporting five to nine open ST positions; 12% have 10 to 14 open positions, 5% have 15 or more. RN percentages are no better: 27% report 5 to 9 open positions, 12% have 10 to 14 open positions, and 11% have 15 or more; only 9% of respondents have no open RN positions, but 19% report no open ST positions.

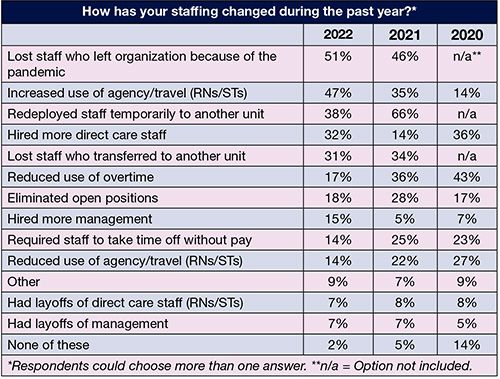

OR leaders reported a number of staffing changes over the past 12 months, the most significant being redeploying staff temporarily to another unit, which dropped from 66% in 2021 to 38% this year, likely reflecting the evolving COVID-19 pandemic. Other strategies used significantly less often this year compared to 2021 include reducing overtime (17% vs 36%), eliminating open positions (18% vs 28%), and requiring staff to take time off without pay (14% vs 25%). Strategies used more often included the use of agency and travel staff (47% vs 35%), hiring more direct care staff (32% vs 14%), and hiring more managers (15% vs 5%).

We asked OR leaders to share successful strategies for recruiting staff. The 254 responses we received related to both recruitment and retention.

Financial. The most common recruitment strategies related to financial reward, proving that money still talks. Strategies include sign-on, relocation, and referral bonuses; higher compensation; loan repayment; and more benefits. One respondent noted: “paying employees what they are worth; they will recruit new employees to your department.”

Culture. OR leaders are focusing on creating a welcoming, nurturing work environment. Flexible scheduling can foster happiness. One respondent noted, “Working with a combination of shorter and longer shifts helps work-life balance.” Another offers 4-, 8-, 10-hour shifts, and one offers no-call positions. Other comments included:

- “Achievements are recognized by the leaders and colleagues.”

- “Trying to be positive and happy.”

Connections. Many OR leaders cited word of mouth, including staff referrals, as an effective recruitment strategy. Other strategies included partnering with schools to serve as clinical sites for RN and ST programs, which promotes a pipeline of staff. Some respondents noted their willingness to hire new graduates and those without OR experience. Other comments included:

- “Work with students during clinical [rotations] and build relationships.”

- “Talk to students early. Show them respect and kindness.”

- “Creative residency programs…competitive wages.”

- “Treat candidates like clients.”

Several reported using social media, including LinkedIn and Indeed.

Education. Respondents cited training and education as valuable strategies, including formal training programs, precepting, and residency programs.

Other strategies included multidisciplinary interviews, shadowing experiences, peer interviews, and staffing committees. A few respondents noted the importance of correctly representing the organization during the interview:

- “Being transparent with applicants as to the size of our facility and types of patients we see.”

- “Being honest about our current situation, both positive and negative.”

- “During the interview process, I walk them through the OR to allow them to see the facility and what we have to offer. They get to meet staff members and see how they interact with each other.”

Respondents noted what was not working (ads and open houses). OR leaders expressed frustration landing new staff; one commented, “I have no strategies. Nothing is working to fill open positions.” Another noted, “Too much competition from travel agencies—their salary and benefit package cannot compare to the full-time hospital RN package.”

A bundle of strategies is more likely to be effective than one. An OR leader listed the following elements: “Networking, culture of department and hospital, engagement with staff on a professional and personal level, emotional intelligence, staff advocacy, and transparency.” Another said: “Having a positive work environment, respect, shared governance, lead mostly by consensus, encourage education.”

Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) can facilitate staff recruitment (and retention), so we asked OR leaders to share their strategies. The most common strategy from the 254 responses was education (including orientation and regular inservices), with more than 40 citing it. One respondent noted, “Education has played an important role in promoting DEI. We have conducted ‘all-staff’ grand rounds with panelists to focus on DEI and psychological safety.”

Some reported that the organization had DEI committees or teams, and several foster open communication and ensure culturally inclusive celebrations.

Others noted the link between DEI and recruitment, with one pointing out the value of being “mindful of it” during the interview process, and another recommending “recruiting applicants from a wide variety of sources.” A few commented that organizations need to have DEI-related goals, and one respondent noted: “Training for staff and leadership, attempt to include as many diverse candidates as qualified for interviews, search outside the regional locale for applicants.”

Other comments included:

- “Diversity and equity are promoted by multiple modalities of communication—written, individual ‘check-ins’, daily huddles, and posted communication on a ‘think board’ so individuals can remain anonymous.”

- “Lead with positivity to enhance a positive culture. Utilize just culture with all staff. Encourage teamwork and collaboration among the team.”

- “Treat all staff with sensitivity and respect to their needs.”

- “Giving the opportunity [for staff] to bring up concerns, whether spoken or written, publicly or privately.”

- “A workplace that supports and values employees from diverse backgrounds. Not just by race, gender, age, religion, disability, and sexual orientation, but by skills, experience, and education.”

Unfortunately, OR leaders do not have a crystal ball they can consult to determine when staffing difficulties will ease, and if volume continues to increase, so will the staffing crunch. Instead, they must rely on their expertise to lead the OR team through challenging times.

The percentage of respondents with a business manager increased from 38% in 2021 to 43% this year. Here are some key results.

Requirements

- Nearly half (46%) of OR leaders require business managers to have a clinical background, significantly higher than last year’s 26% and the 29% reported in 2020 and 2019. It will be interesting to see if this trend continues.

Most business mangers (43%) are required to have a master’s degree in business, up from 31% in 2021. In all, 61% are required to have some kind of master’s degree.

Salary

- Business mangers’ salaries were fairly consistent with 2021; 37% earn more than $100,000, comparable to last year’s 40%.

- The second more common reported salary range was $70,000 to $79,999 (15%).

Responsibilities

- The number of direct reports for business managers continues to trend upwards, with 35% having 5 to 9 and 33% having 3 to 4, compared to 29% and 22%, respectively, in 2021. Only 8% have no direct reports, down from 12% last year.

- The top three areas of responsibilities for business mangers are financial analysis and reporting (63%), annual budget (62%), and value analysis and product selection process (57%). The first two percentages are significantly lower than last year. In addition, purchasing OR supplies and equipment fell from 72% in 2021 to 54% this year.

- Interesting shifts from 2021 include increased percentages for surgical services information systems (44% vs 36%) and quality improvement (23% vs 19%), and decreased percentages for billing and reimbursement (41% vs 58%) and OR scheduling (39% vs 47%).

Survey: ASC leaders experience persistent staffing challenges in face of rising volume

By: Cynthia Saver

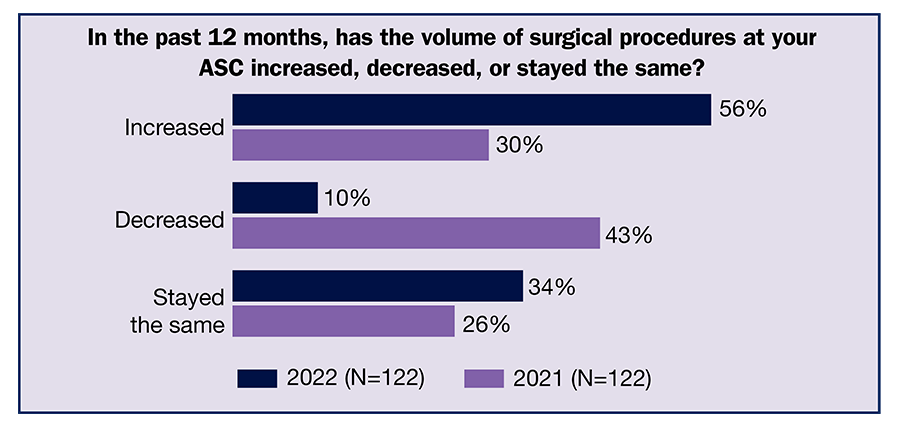

As organizations adapt to COVID-19 and the number of severe cases eases in many areas of the country, leaders in ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) are seeing a significant uptick in volume of surgical procedures, according to the 2022 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey. More than half (56%) reported increased volume in the past 12 months, nearly double 2021’s 30%. Only 10% reported decreased volume, down from 43% last year.

But this positive report of higher volume is tempered by escalating staffing challenges. ASC leaders report increases in turnover and open positions for both RNs and surgical technologists (STs). For example, the percentage of respondents reporting an increase in the number of RN open positions rose from 40% in 2021 to 50% this year, and for STs, the percentage jumped from 28% to 42%.

Other key survey findings include:

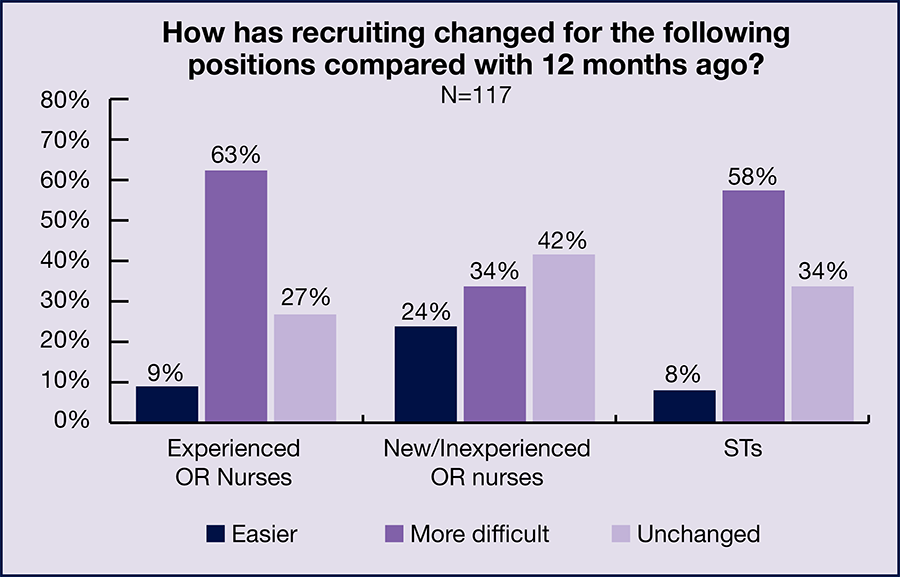

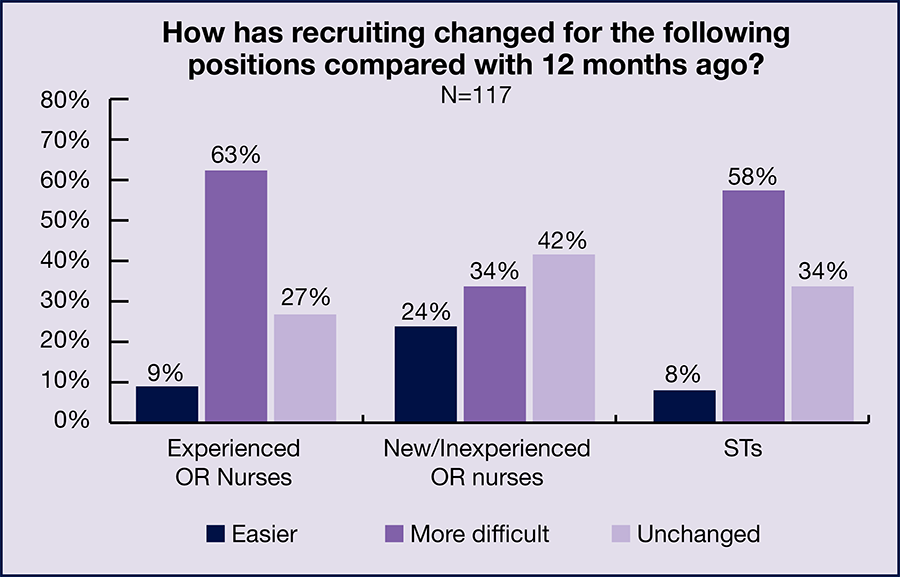

- The ability to recruit new staff remains a challenge for ASC leaders. Nearly two-thirds (63%) reported that recruiting experienced OR nurses is more difficult than 12 months ago, compared to 56% in 2021 and 50% in 2020.

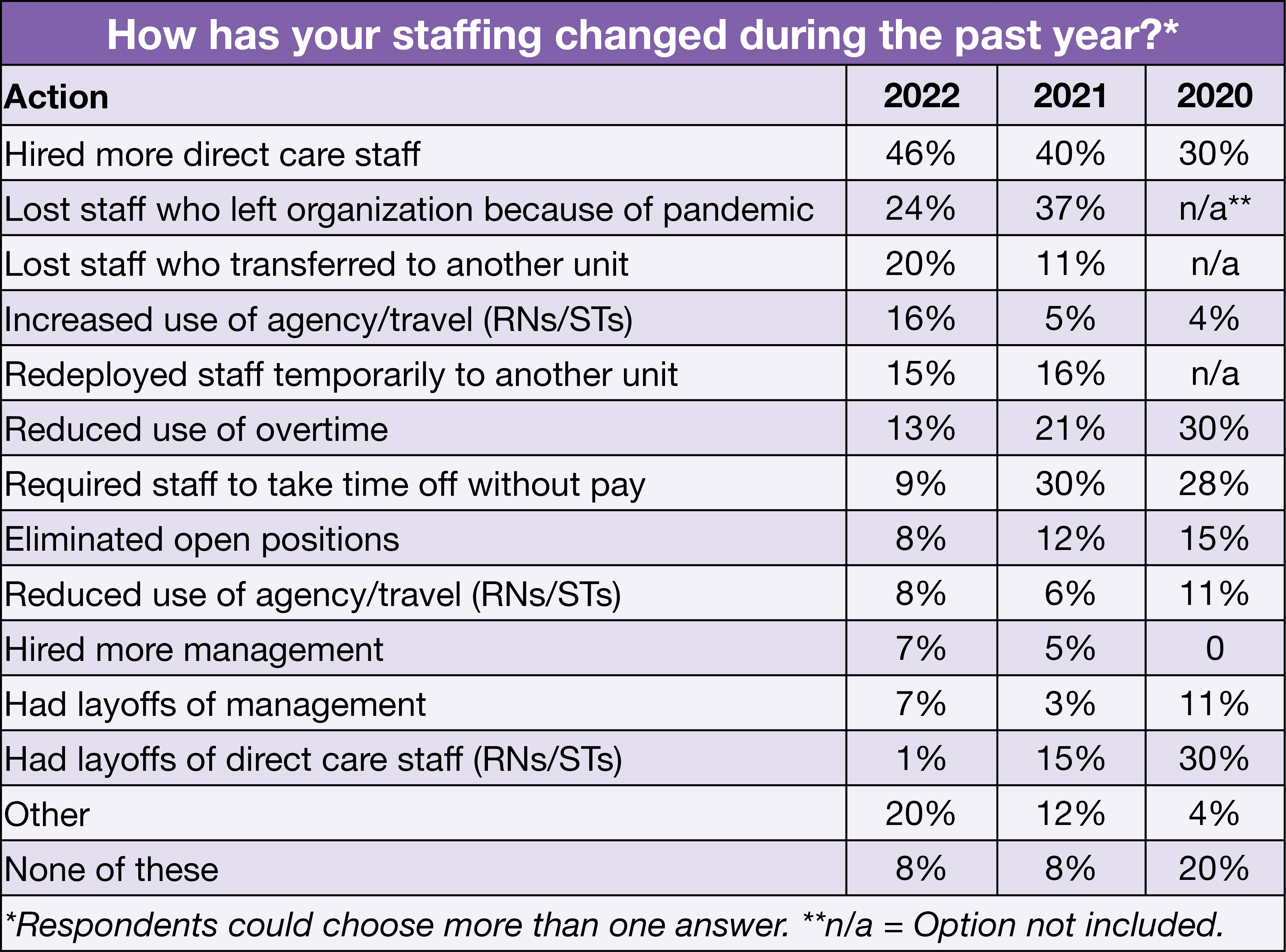

- Despite recruitment challenges, nearly half (46%) hired more direct care staff in the past year.

- ASC leaders continue to lose staff as a result of the pandemic: 24% reported staff left the organization because of it, although this percentage is significantly less than the 37% reported in 2021.

This article focuses on findings related to staffing. (Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.) Results related to ASC leaders’ compensation, scope of responsibility, and job satisfaction will appear in the October issue of OR Manager.

The numbers for turnover and open positions show the seriousness of the staffing situation for many ASC leaders.

Nearly half (46%) of respondents reported RN turnover had increased in the last year, comparable to 2021’s 49%, but far higher than the 24% from 2020. Only 8% reported decreased turnover. This bleak outlook continues for STs. The percentage of respondents who reported ST turnover had increased from 28% last year to 37%; as with RNs, only 8% reported a reduction in turnover.

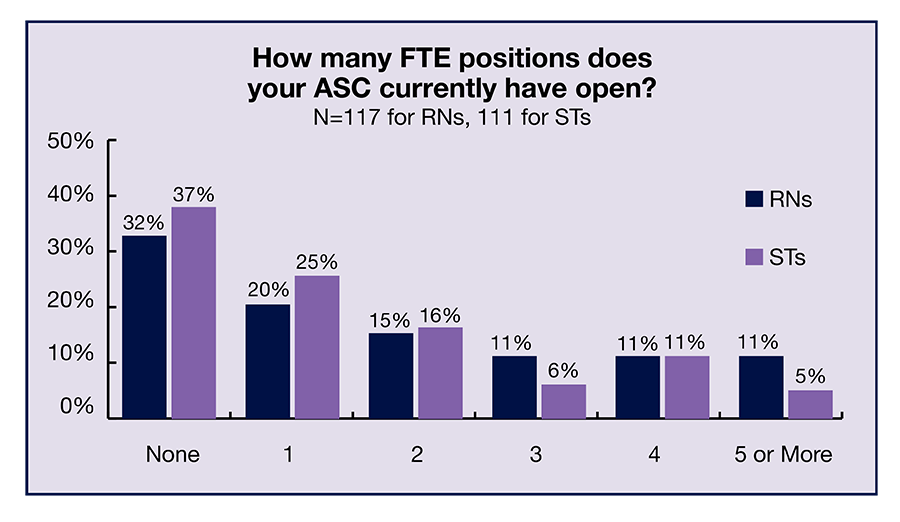

As noted earlier, the number of open positions increased for both RNs and STs, and few ASC leaders reported a decrease for either group (8% for RNs and 7% for STs). Nearly a third (32%) of respondents reported having no current open full-time equivalency (FTE) RN positions; 20% had 1 open position, and 15% had 2 openings. The percentages for 3, 4, and 5 or more open positions were all 11%. In all, 68% had at least one open position. For STs, 63% had at least 1 open position. The breakdown was: 37% had no open ST positions, 25% had 1, 16% had 2, 6% had 3, 11% had 4, and 5% had 5 or more.

ASC leaders are finding it challenging to replace staff. According to a report from NSI Nursing Solutions, Inc, it takes an average of 111 days to fill an open OR nurse position. This is comparable to what OR Manager survey respondents reported: 115 days for RNs and 109 days for STs.

The percentage of those reporting that recruitment of new or inexperienced OR nurses had become more difficult compared to 12 months ago jumped from 19% in 2021 to 34% this year, with 24% reporting it was easier. Only 9% of respondents reported it had become easier to recruit experienced OR nurses, unchanged from 2021. ASC leaders also are finding ST recruitment daunting, with 58% (up slightly from 55% in 2021) reporting this had become more difficult, and only 8% (vs 6% in 2021) noting it was easier.

As in 2021, the most common staffing change during the past year was hiring more direct care staff, reported by 46% of respondents, continuing an upward trend (40% in 2021 and 30% in 2020). The next most commonly reported staffing changes were losing staff who either left the organization because of the pandemic (24%, down from 37% in 2021) or transferred to another unit (20%, up from 11% in 2021). Other significant changes in this area included a higher percentage reporting increased use of agency and travel staff (16% vs 5%) and decreases in reduced use of overtime (13% vs 21%) and eliminating open positions (8% vs 12%). The biggest drop was seen in requiring staff to take time off without pay, which fell from 30% in 2021 to 9% this year.

Nearly half (48%) of respondents work in a physician-owned ASC, 29% in a joint-venture ASC, 14% in a hospital-owned ASC, and 5% in a corporate or LLC ASC.

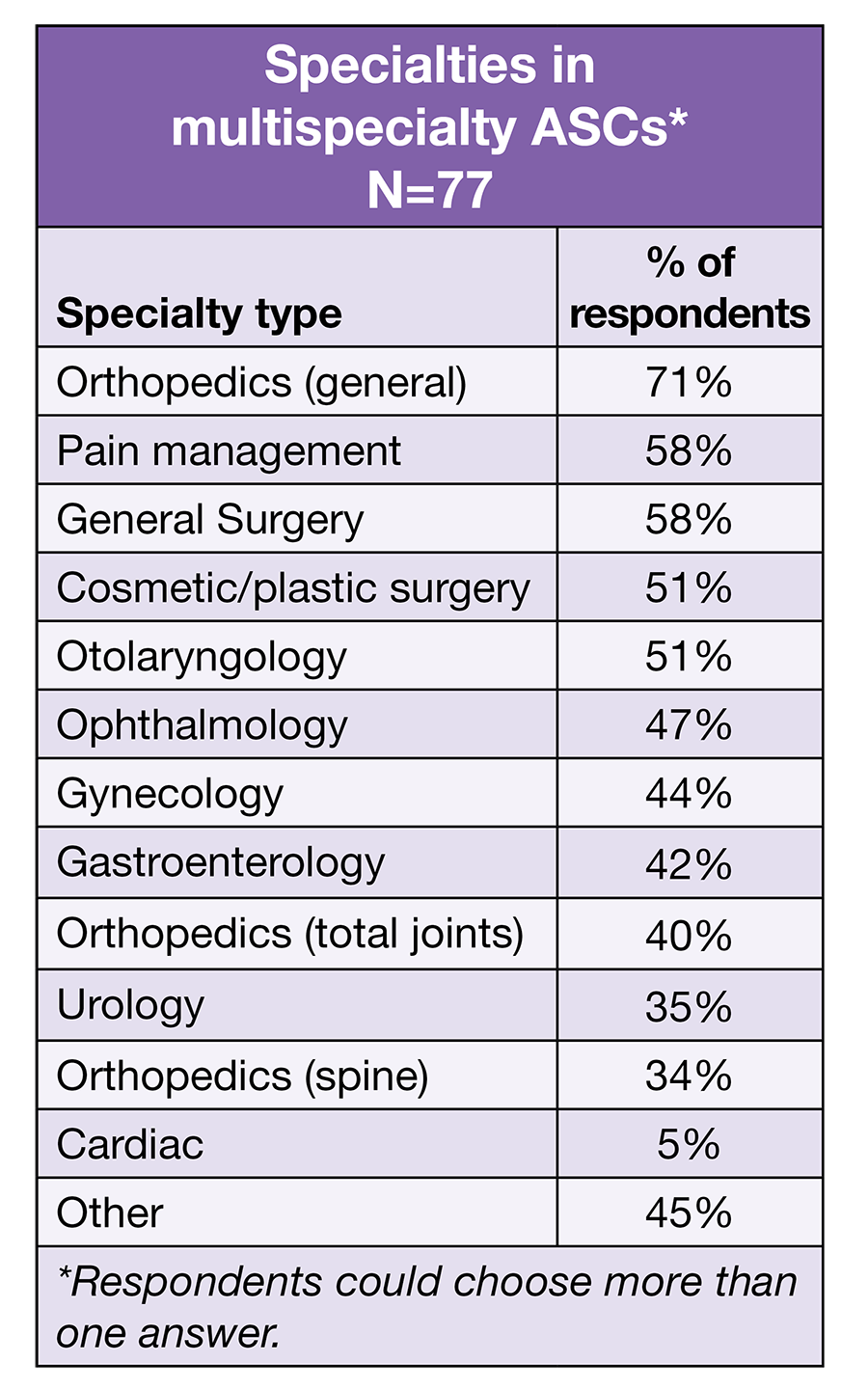

Most respondents (60%) start their day in a multispecialty rather than single-specialty ASC. As in 2021, ophthalmology was the most common single specialty, cited by 42% of ASC leaders, followed by orthopedics (17%) and general surgery (11%). No other specialty received more than 10%.

When ASC leaders who work in multispecialty ASCs were asked to choose the specialties their facility offers, most included general orthopedics (71%, compared to 81% in 2021). Specialties receiving more than 50% responses were pain management (58%), general surgery (58%), cosmetic/plastic surgery (51%), and otolaryngology (51%). For respondents working in either single specialty or multispecialty ASCs, podiatry was the most commonly cited specialty that was not on the list of options they could choose from.

Only 10% reported the volume of surgical procedures had decreased in the past 12 months (much lower than the 43% from 2021), with 34% (vs 26% in 2021) saying it had not changed. Interestingly, although volume had increased for most respondents, the average annual volume of surgical procedures (including endoscopies) was 4,242, slightly lower than last year’s 4,801. This may be because of the wide range in volumes reported (6 to 30,000).

Because staffing is such a challenge, we asked ASC leaders to share strategies they have found successful for recruiting staff. Of the 112 responses we received, the most common was “word of mouth,” which was cited by 22 ASC leaders. Other strategies included bonuses, social media, compensation, staff referral, partnering with local RN and ST schools, and offering an attractive schedule (eg, flexibility, no holidays, weekends, or call). One ASC leader trains new graduates, adding, “Writing the job posting so that specific skills/attributes are highlighted (fast-paced environment, efficient multi-tasking, etc); rather than focusing recruitment on specific experience needed, focus on the right personality and be very clear that training will be provided.”

Some respondents took a broader view in answering the question by honing in on the importance of the work environment. For example:

- “Creating and maintaining an employee centered environment. It is important to support, encourage, and lead staff, as well as incorporating fun.”

- “Listening to what staff have to say. Engaging them in decision making and finding new staff that will fit into our environment and staffing mix.”

- “Positive work environment centered around growth and investment in the employee.”

Promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) also is key for staff recruitment and retention, so we asked ASC leaders to share their strategies in this area. Education, training, communication, and committees were the most common items included in the 112 responses. One mentioned using job boards that are specifically geared towards DEI, and another noted the benefit of DEI, writing, “We’re hiring more and more staff with diverse backgrounds and alternate native languages. This has been a great benefit to our facility.”

Here are some examples of comments from those who listed more than one strategy:

- “Have DEI council rep update team monthly on council initiatives. Have DEI activities they can do to earn DEI t-shirts. Email notices that contain educational info around different cultures. Roundtable talks and fireside chats that highlight different DEI topics each month—is a game changer in terms of gaining insight and understanding, everyone should do this!”

- “Aware of unconscious bias, acknowledge holidays of all cultures, develop a training program specific to our center, and encouraging ongoing feedback and assess company policies.”

- “Hiring for diversity, role modeling inclusivity, providing positive feedback and holding staff accountable for behavior.

This year’s survey shows that although ASC leaders are seeing more volume in procedures, staffing challenges remain at the forefront. It is unsure when the situation will improve.

Survey: Some improvement in satisfaction, but stagnant compensation

By Cynthia Saver

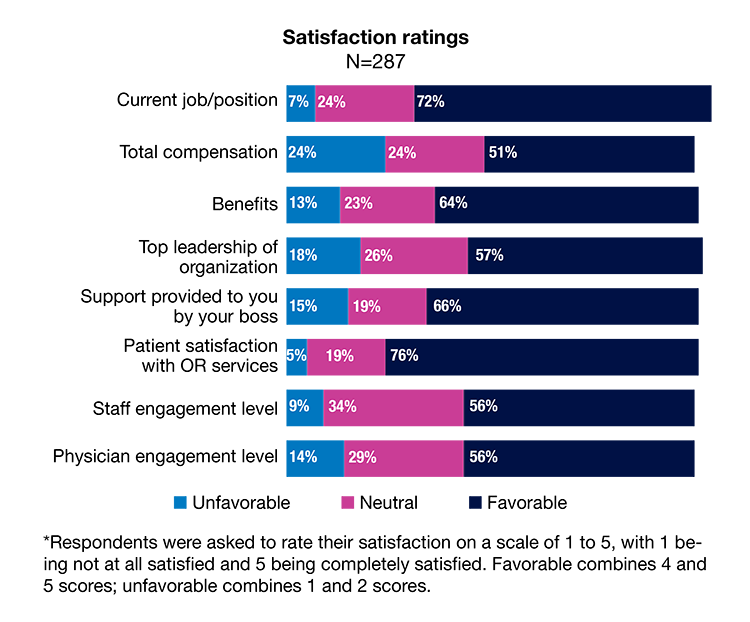

As the response to the COVID-19 pandemic becomes embedded in hospitals, OR leaders’ satisfaction with their job is improving, according to the 2022 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey. Nearly three-fourths (72%) view their current job favorably, up from 64% last year and just below 2020’s 77%. However, satisfaction with many other areas remains stagnant with only slightly more than half (56%) reporting favorable levels of engagement for both staff and physicians.

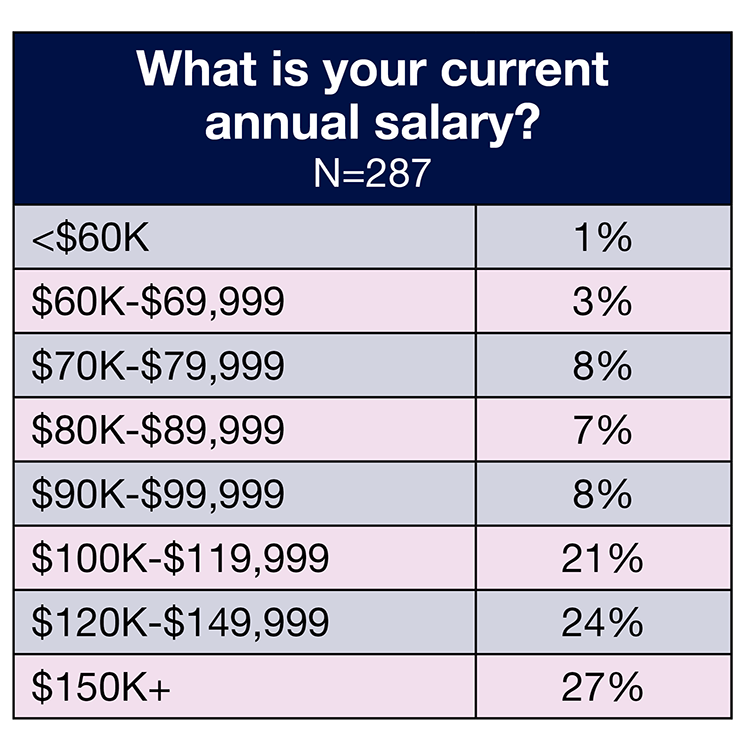

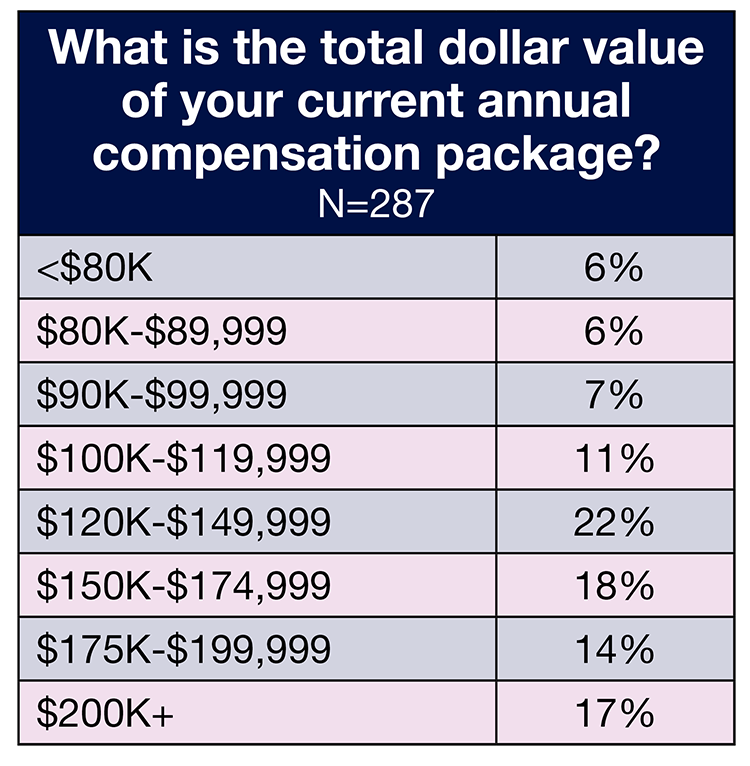

Compensation also is stagnant with OR leaders’ salaries and total compensation comparable to 2021 and 2020. Roughly one-fourth (27%) of respondents reported earning $150,000 or more, slightly below both 2021 (31%) and 2020 (30%), and 17% receive a total compensation of $200,000 or more, up slightly from 2021 (15%), but unchanged from 2020.

Other key findings from the survey include:

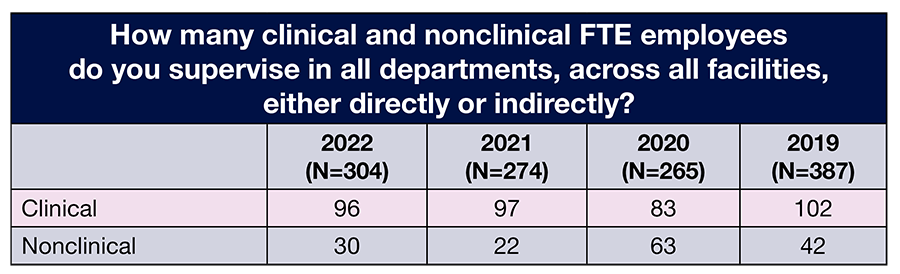

- The average number of full-time equivalent (FTE) employees that OR leaders supervise is 113, compared to 119 in 2021 and 146 in 2020.

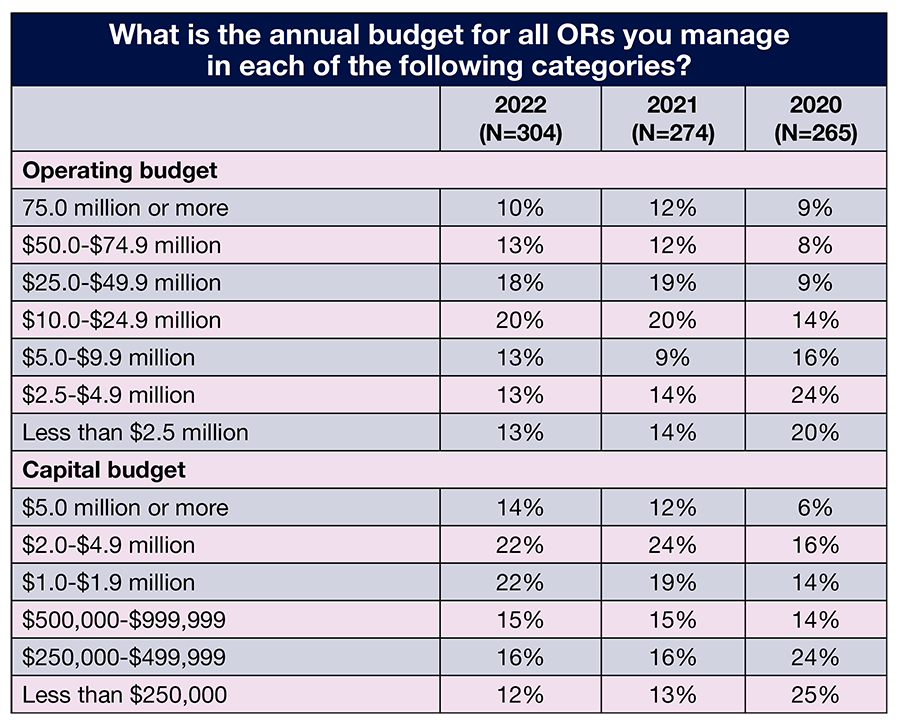

- The percentage of those who report managing an operating budget between $25 million and $4.9 million has been steady the past 3 years: 64% this year, 62% in 2021, and 63% in 2020.

- As in 2021, staffing is OR leaders’ top concern when it comes to the future of perioperative nursing.

- In all, 45% of respondents plan to stay with their current employer 5 years or more, with 27% planning to stay 2 years or less.

This article delves into more findings related to OR leaders. (Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.) For results related to staffing, see “Surgical volume returns for many ORs, but staff shortages remain,” OR Manager, September 2022, pp 1, 5–9.

Respondents saw little change in their salaries over the past year. In all, 72% reported earning an annual salary of $100,000 or more this year, compared to 78% in both 2020 and 2021. Only 1% (vs 4% in 2021) earn less than $60,000.

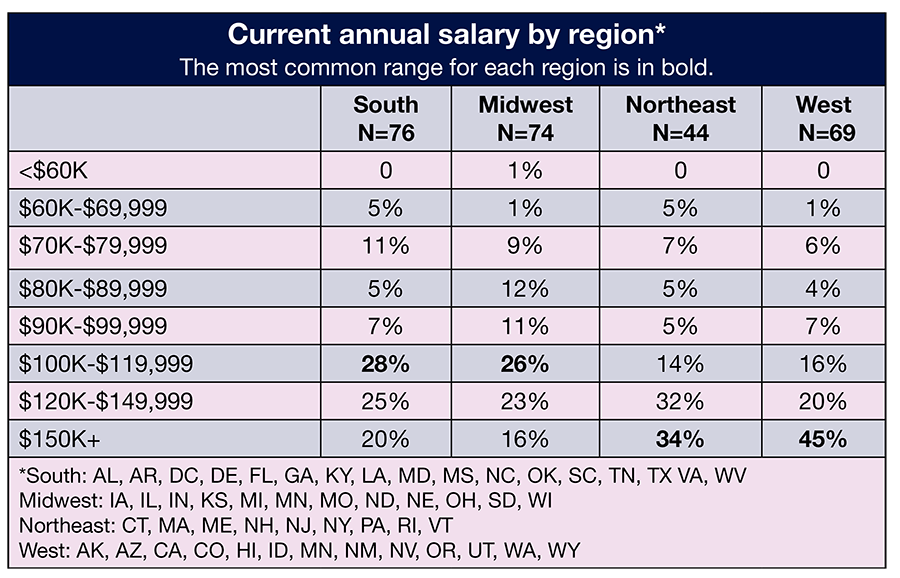

As expected, salaries varied by job title. For example, the percentage of those earning $150,000 or more a year (the highest option respondents could choose) by job title were 56% for vice president or chief nurse executive, 44% for administrator or administrative director, 33% for director or assistant director, and 6% for nurse manager. This range also was the one most commonly reported by vice presidents or chief nurse executives, administrators or administrative directors, and directors or assistant directors. The most common salary range for nurse managers was $100,000 to $119,999 (32%).

Across regions, respondents in the West and Northeast most often reported earning $150,000 or more (45% for the West and 34% for the Northeast). The range of $100,000 to $119,999 was the most common for those in the South (28%) and Midwest (26%).

Total compensation also stayed relatively flat. The most commonly reported range remained the same: $120,000 to $149,000 (22% in 2022 vs 25% in 2021), followed by $150,000 to $174,999 (18%). Only 6% reported a total compensation of less than $80,000.

The most common ranges for total compensation by job title were $200,000 or more for vice president or chief nurse executive (59%) and for administrator or administrative director (28%), and $150,000 to $174,999 for director or assistant director and nurse manager.

The most common total compensation range for those working in the Midwest and South was $120,000 to $149,999 (28% of Midwest respondents and 22% of South respondents). Most (23%) of those in the Northeast earn $175,000 to $199,999, and the top range in the West (35%) was $200,000 or more.

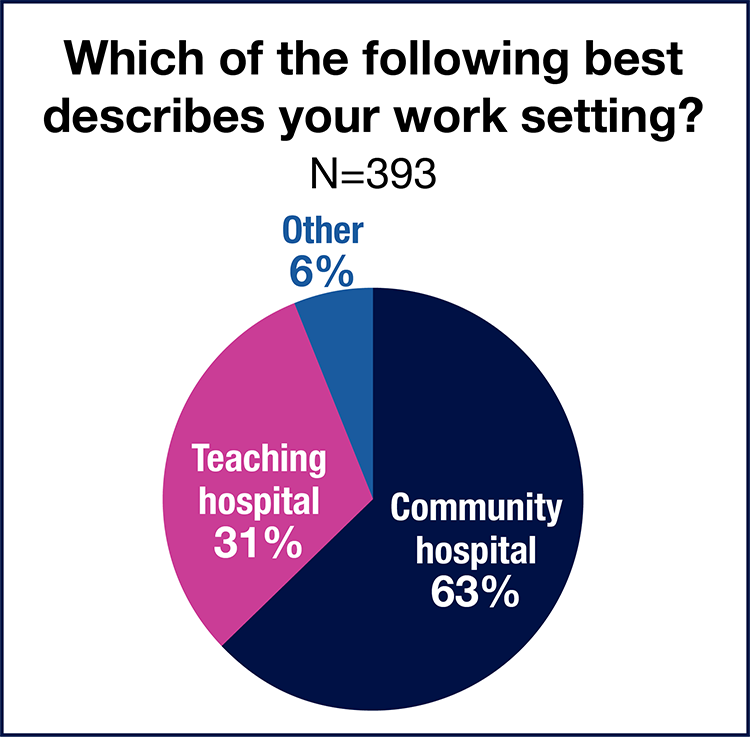

As has traditionally been true, OR leaders working in teaching hospitals earn more than those in community hospitals. More than half (56%) of respondents in teaching hospitals earn $150,000 a year or more (vs 54% in 2021) in total compensation, compared to 44% in the community setting (vs 47% in 2021). The most common total compensation range for community hospital respondents was $120,000 to $149,000 (25%); for their teaching hospital colleagues it was $159,000 to $174,999 (24%).

As in 2021, 63% of respondents had received a raise in the past 12 months, compared to 68% in 2020. The average raise was 4.1% (vs 3.3% in 2021), with 3% being the most common response. Both of these are lower than the 2021 consumer price index of 7%.

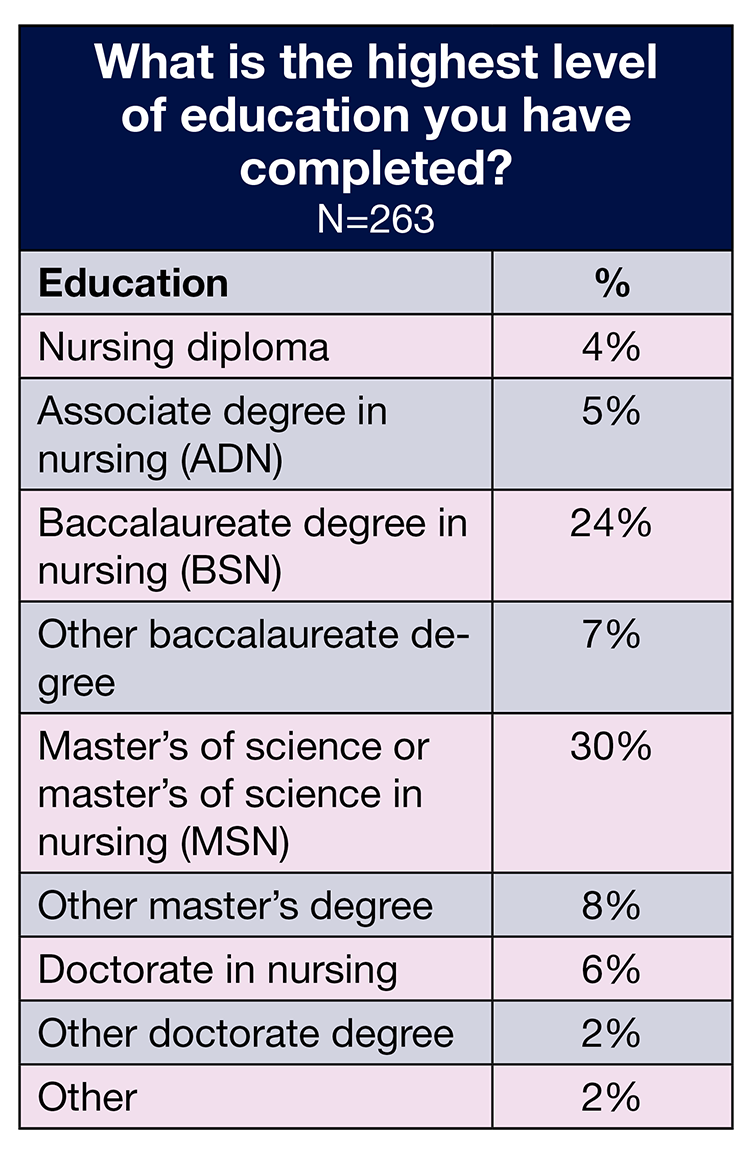

Most respondents chose either nurse manager (37%) or director/assistant director (36%) from a list of title options, followed by administrator/administrative director (12%), and vice president/chief nurse executive (11%).

OR leaders supervise an average of 96 clinical FTE positions, essentially unchanged from 97 in 2021, and 30 nonclinical positions, up from 22 positions in 2021. Most respondents (29%) oversee 1 to 5 ORs, slightly higher than last year’s 22%. About one-fourth (26%) are in charge of 6 to 10 ORs, comparable to previous years (25% in 2021 and 21% in 2020). Only 5% oversee more than 35 ORs.

Reported budget responsibilities were consistent with 2021 findings. In all, 23% manage an operating budget of $50 million or more (vs 24% last year), and 38% manage a budget of $10 million to $49.9 million (vs 39% last year).

Consistency was also found for the capital budget. More than a third (36%) of respondents oversee a budget of $2 million or more, the same as in 2021, and only 28% manage a budget of $499,999 or less, compared to 29% last year.

This year saw a return to greater job satisfaction, with the 72% favorable rating aligning with prepandemic levels (70% in 2019). One in five (20%) were completely satisfied with their current job, up slightly from last year’s 18%. Only 7% rated their satisfaction as unfavorable.

More respondents had a favorable view of their total compensation compared to 2021 (51% vs 45%), but satisfaction was still lower than 2020 (60%). OR leaders felt more positive about their benefits, with nearly two-thirds (64%) giving this a favorable rating.

Continuing a trend in recent years, satisfaction with support provided by the respondent’s boss remained relatively high, with a favorable rating of 66% (vs 70% in 2021). Although satisfaction with the top leadership of the organization was unchanged from last year (57%), the percentage of those who were unsatisfied declined from 24% to 18%.

Another continuing trend was the high favorability rating for the criterion of patient satisfaction with OR services—76% vs 81% in 2021. Only 5% gave this an unfavorable rating.

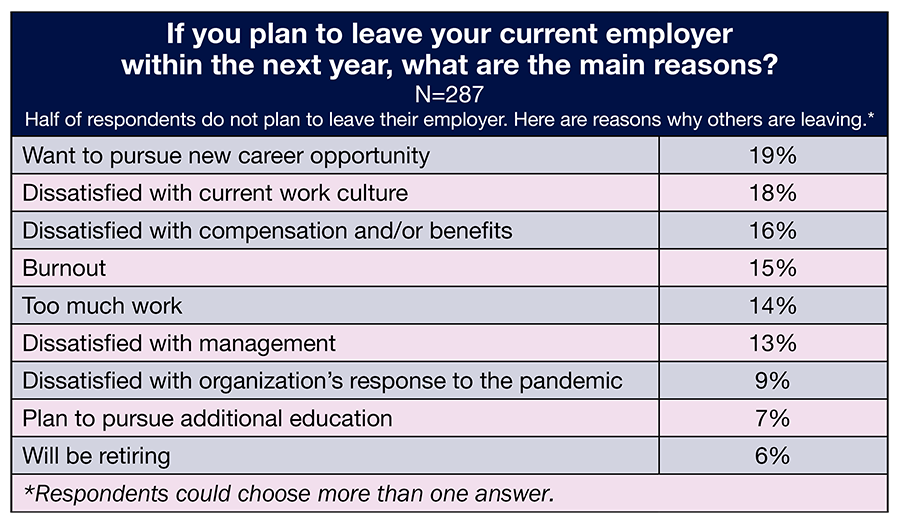

The pandemic prompted many to re-think their careers, and half of respondents seem to be open to leaving their employers within the next year. The most common reason cited for leaving was to pursue a new career (19%, up from 14% in 2021); it is unknown whether this means in a different field or a new career within nursing. Other common reasons for leaving included dissatisfaction with the current work culture (18%), dissatisfaction with compensation and/or benefits (16%), and burnout (15%). Two reasons for leaving that had significant percentages changes were too much work, which increased from 9% last year to 14% and dissatisfaction with the organization’s response to the pandemic, which increased from 3% to 9%.

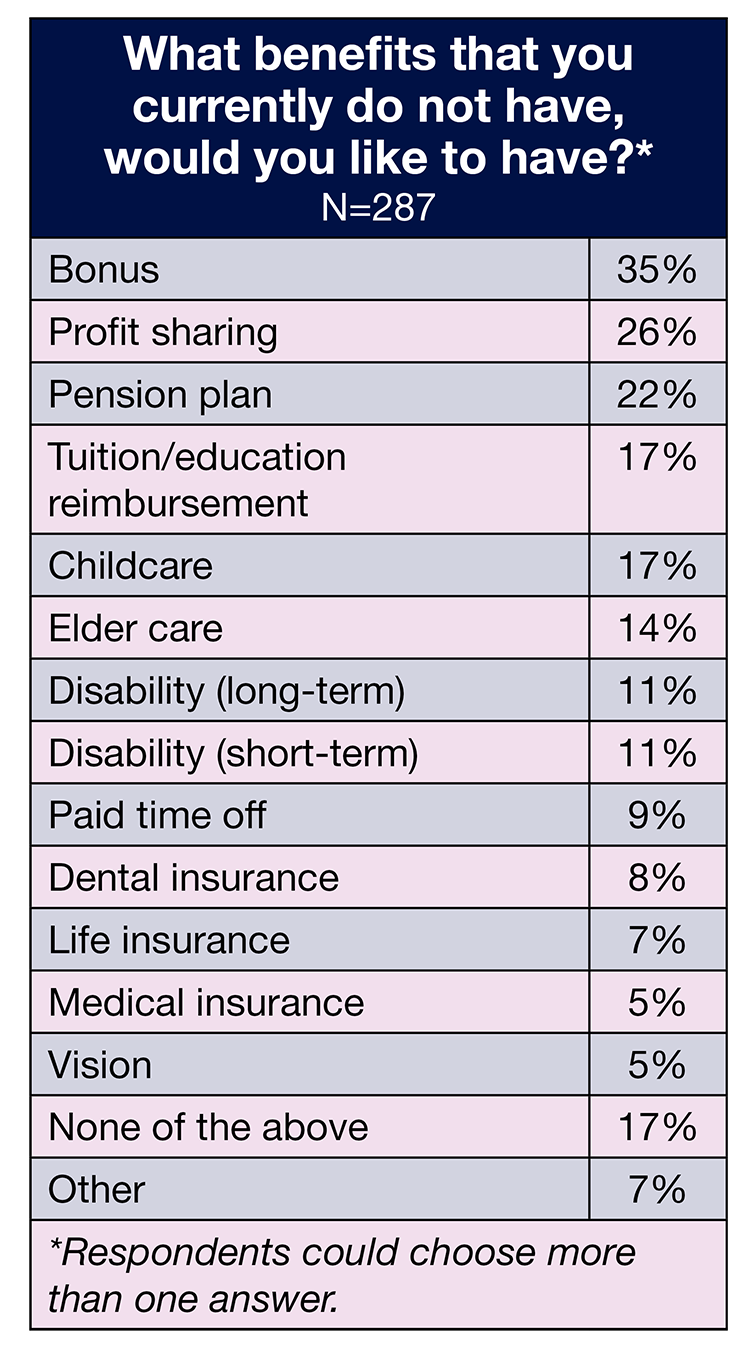

Benefits may help lessen the likelihood of OR leaders leaving, so we asked respondents to select from a list of benefits they would like to receive if they did not currently have them. Unsurprisingly, money-related benefits took the top four spots: bonus (35%, down from 48% in 2021), profit sharing (26%), pension plan (22%), and tuition/education reimbursement (17%). Significant increases occurred in childcare, which jumped from 8% to 17%, and disability. Both short- and long-term disability benefits were cited by 11% of respondents, versus 3% for short-term and 5% for long-term in 2021.

This year saw a return to greater job satisfaction, with the 72% favorable rating aligning with prepandemic levels (70% in 2019). One in five (20%) were completely satisfied with their current job, up slightly from last year’s 18%. Only 7% rated their satisfaction as unfavorable.

More respondents had a favorable view of their total compensation compared to 2021 (51% vs 45%), but satisfaction was still lower than 2020 (60%). OR leaders felt more positive about their benefits, with nearly two-thirds (64%) giving this a favorable rating.

Continuing a trend in recent years, satisfaction with support provided by the respondent’s boss remained relatively high, with a favorable rating of 66% (vs 70% in 2021). Although satisfaction with the top leadership of the organization was unchanged from last year (57%), the percentage of those who were unsatisfied declined from 24% to 18%.

Another continuing trend was the high favorability rating for the criterion of patient satisfaction with OR services—76% vs 81% in 2021. Only 5% gave this an unfavorable rating.

The pandemic prompted many to re-think their careers, and half of respondents seem to be open to leaving their employers within the next year. The most common reason cited for leaving was to pursue a new career (19%, up from 14% in 2021); it is unknown whether this means in a different field or a new career within nursing. Other common reasons for leaving included dissatisfaction with the current work culture (18%), dissatisfaction with compensation and/or benefits (16%), and burnout (15%). Two reasons for leaving that had significant percentages changes were too much work, which increased from 9% last year to 14% and dissatisfaction with the organization’s response to the pandemic, which increased from 3% to 9%.

Benefits may help lessen the likelihood of OR leaders leaving, so we asked respondents to select from a list of benefits they would like to receive if they did not currently have them. Unsurprisingly, money-related benefits took the top four spots: bonus (35%, down from 48% in 2021), profit sharing (26%), pension plan (22%), and tuition/education reimbursement (17%). Significant increases occurred in childcare, which jumped from 8% to 17%, and disability. Both short- and long-term disability benefits were cited by 11% of respondents, versus 3% for short-term and 5% for long-term in 2021.

When asked, “what is your biggest concern about the future of perioperative nursing?” the answer from OR leaders was clear—staffing. Of the 254 respondents, nearly all mentioned a staffing-related issue. The most common worry was not having enough staff, with comments touching on recruitment, training, and retention. One noted, “As surgical volumes will always be present and are growing in many cases, having adequate numbers of competent, trained staff to prevent reduction in services is a big concern.”

Other staffing-related responses included:

- “More widespread demands for labor as more facilities increase surgeries and not enough well-trained staff or educators to train new staff and maintain competency.”

- “I worry that staff will continue to be asked to do too much with too little.”

- “The growing void of mid-level experienced RNs. There’s a huge experience gap between new grad/novice RNs and late-stage/retiring RNs.”

- “My biggest concern is the lack of focus-driven individuals with planned longevity in this career field. Many staff members plan to work in this area 5 years or less and move onto other areas.”

Some respondents specified the pipeline issue, with one commenting, “Lack of exposure to perioperative services in nursing school has led to a decline of RNs pursuing the periop career path; this will continue to impact the specialty until periop becomes part of the curriculum.”

One respondent wondered if most nurses will turn to agency employment and noted that younger nurses are unlikely to stay in management positions because of the long hours and lack of work-life balance.

Other concerns included workplace violence, physician recruitment, keeping up with technology, and staying competitive.

A few respondents commented on the nursing profession in general:

- “Individuals don’t want to go into nursing because of the long hours and no home life.”

- “My concern is more for the profession of nursing. The pandemic has really worn on the psyche of everyone, especially nurses. We are burnt out and exhausted and don’t have the energy to promote ourselves and our profession as we once did, and this is giving a negative perspective to young people who are currently deciding on a career.”

This comment sums up many OR leaders’ concern: “Staffing. Where are all the OR nurses?”

OR leaders continue to face a challenging work world, but their earnings are flat, and staffing headaches are unlikely to ease anytime soon. These leaders are known for their ability to rise to any challenge, and hopefully, this will continue into a future where patients will continue to depend on them to facilitate optimal care.

Survey: Relatively flat compensation in an era of many stressors

By Cynthia Saver

Compensation has remained relatively flat for leaders in ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs), according to the 2022 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey, even as leaders face ongoing stressors. This is reflected in the 40% of respondents who reported a total current annual compensation of $120,000 or more—unchanged from 2021. Ongoing stress is reflected in the reasons given by respondents who plan to leave their employers within the next year—one-fourth cited burnout, nearly double last year’s 14%, and 17% cited too much work, up from 12% in 2021.

Other key findings include:

- Two-thirds of respondents had received a raise in the past 12 months. The average raise was 4.24%, significantly lower than the 2021 consumer price index of 7%.

- The percentage of respondents who view their current job/position as favorable dropped slightly, from 78% in 2021 to 73% this year, although the percentage of those with a favorable view of the support provided by their boss rose from 64% to 70%.

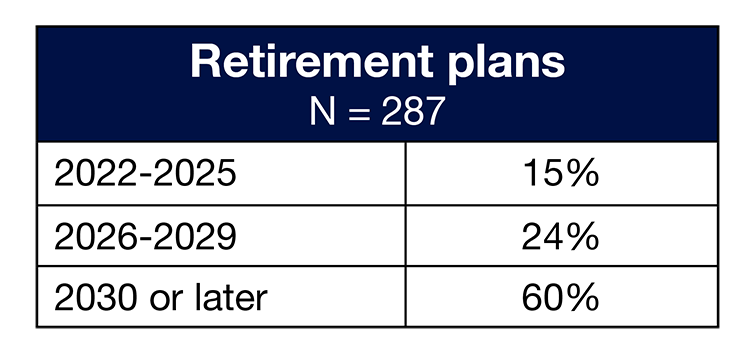

- Nearly three-fourths (71%) plan to retire in 2030 or later, up from 59% in 2021.

- More than half (55%) of respondents’ plan to stay with their current employer 5 years or more, but 24% plan on staying 2 years or less.

Here is a closer look at other findings. (Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.) For results related to staffing, see “Survey: ASC leaders experience persistent staffing challenges in face of rising volume” (OR Manager, September 2022, pp 24–26).

In all, 58% of respondents report an average annual salary of $100,000 or more, up slightly from 51% in 2021, but comparable to 2020’s 59%. The most common salary ranges were $100,000 to $119,999 (23% vs 27% in 2021) and $120,000 to $149,999 (22% vs 18% in 2021). The percentage of those earning $150,000 or more rose from 6% last year to 13%. Among vice president or chief nurse executive respondents, 25% chose each of the following three salary ranges: $100,000 to $119,999; $90,000 to $99,999; and $70,000 to $79,999. The most common salary range for administrator or administrative director was $120,000 to $149,999 (21%); 30% of directors or assistant directors also chose this range. Nurse managers most commonly chose $90,000 to $99,999 or $100,000 to $119,999 (25% for each range).

Most ASC leaders in the Northeast (29%) chose the highest salary range ($150,000 or more). Those in the West most commonly chose $120,000 to $149,999 (43%), and those in the Midwest most commonly chose $100,000 to $119,999 (35%). The most common salary range for those in the South was $90,000 to $99,999.

The most common annual total compensation was $120,000 to $149,999 (26%), followed by $90,000 to $99,999 (20%). Only 3% earn $200,000 or more (unchanged from 2021), and 3% earn less than $80,000 (vs 12% in 2021).

The most common range for total compensation by job title were $90,000 to $99,999 for vice president or chief nurse executive (50%), $100,000 to $119,999 and $150,000 to $174,999 for administrator or administrative director (21% for each range), and $120,000 to $149,999 for director, assistant director, or nurse manager (35%).

Most ASC leaders in the Midwest (32%) and Northeast (24%) chose 120,000 to $149,999 as the range of their total compensation. The most common choice for the West was $100,000 to $119,999 (33%), and for the South, it was $90,000 to $99,999 (31%).

Respondents supervise an average of 35 full-time equivalent (FTE) positions, up slightly from 32 in 2021. The average was 27 for clinical and 9 for nonclinical positions.

Nearly half reported they did not know their ASCs’ annual operating budget. One-fifth oversee an operating budget of $1.9 million or less (vs 7% in 2021), and about one-fourth (24%) oversee a budget of $5 million or more (vs 25% in 2021). The most common range was $1 million to $1.9 million (13%), followed by $10 million to $14.9 million (12%). Nearly half (47%) said their operating budget had increased in the past 12 months, and the same percentage reported it had remained the same.

Most respondents (80%) oversee one to five ORs, up from 74% in 2021 but comparable to the 81% reported in 2020. Only 7% have 10 or more ORs under their purview.

As noted earlier, there was a slight drop in satisfaction with current job/position, with 73% giving this a favorable rating, compared to 78% last year; only 16% said they were “completely satisfied.” Patient satisfaction with OR services once again had the highest satisfaction level, although favorability dropped from 96% in 2021 to 88% this year.

Another significant change was the drop in satisfaction with staff engagement from 76% to 69%, with only 21% saying they were completely satisfied. In addition, satisfaction with top leadership shifted slightly: 9% of respondents gave this an unfavorable rating, down from 17% in 2021. Most of the change, however, moved to the neutral category; the favorable rating was 62% compared to 66% last year.

Most respondents do not plan to leave their employer within the next year, but for those who do, burnout (25%) and too much work (17%) were the top reasons. Some want to pursue a new career opportunity (15%, up from 8% in 2021), while others say they are dissatisfied with the current work culture (14%) or compensation and/or benefits (also 14%).

Given that benefits may be a reason for leaving, we asked respondents to select which benefits they would like to receive if they did not currently have them. Money-related benefits took the top four spots: profit sharing (39%), bonus (31%), tuition/education reimbursement (26%), and pension plan (22%).

Overall demographics are listed in the infographic (p 27). The average age of the respondents was 48 years (vs 51 in 2021), slightly lower than the 52 years reported by the 2020 National Nursing Workforce Survey.

ASC leaders spend an average of 45 hours at work each week (similar to 2021’s 47), with a range of 30 to 70. Most respondents reported 5 years or less of experience (29%), with 24% having either 6 to 10 or 11 to 15 years of experience. About one-fifth (22%) reported 16 or more years of experience. Only 10% plan to retire between 2022 and 2025, although that still adds up to a significant loss of expertise.

Diversity is limited among ASC leaders. The vast majority of respondents (84%) chose White as their race or ethnicity. None chose Hispanic/Latinx, and the percentages for other groups were: 1% for Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, 2% for American Indian/Alaska Native, 3% for African American/Black, and 4% for Asian.

The baccalaureate degree in nursing remains the most common highest degree held by ASC leaders who responded to the survey (32% vs 42% in 2021). More than one-fourth (26%) hold a master’s degree, compared to 20% last year and 29% in 2020. Only 2% have a doctorate degree.

Of the title options provided in the survey, 33% chose administrator/administrative director, and 32% chose director/assistant director, followed by 29% for nurse manager, and 4% for vice president/chief nurse executive. Most respondents live in the South (37%), with 27% in the Midwest, and 18% in the West and in the Northeast.

More than 100 respondents (112) shared an answer to the question: “What is your biggest concern about the future of perioperative nursing?” As expected, staffing concerns topped the list of comments. As one respondent noted, “Staffing safely with competent nurses is a major concern for the future of perioperative nursing.”

Other insights included:

- “Experienced nurses are harder and harder to find. It is difficult to compete for nurses with large hospital systems that can afford higher wages [and] sign-on and retention bonuses.”

- “Staffing issues as a result of burnout, work-from-home jobs, relatively low pay for the amount of hard work that is put into it (wages not keeping up with inflation).”

Several comments related to one or both ends of the staffing pipeline:

- “Brain-drain as experienced teammates retire with inexperienced teammates taking their place.”

- “Schools have got to bring perioperative nursing back into their program.”

- “How do we get people interested in healthcare? The numbers in schools do not meet the demand, and veterans are getting burned out of the profession.”

Additional concerns included reimbursement, compliance, data interoperability, mobile application support, increased cost of supplies and operations, and “the ability to remain financially solvent.”

Financial-related comments included:

- “Medicare reimbursement for ASCs cannot keep up with hospital reimbursement. I am worried about losing good staff to the hospital.”

- “Too many reimbursement cuts by insurances and government. With cuts rising and costs rising, no way for small ASCs to keep up.”

- “Pay does not equal knowledge base and skill level, continually fighting for rate increases for staff.”

A few addressed the profession in general, with one noting, “Lack of commitment to the profession as a whole.”

Compensation and challenges have remained consistent for ASC leaders over the past year. It remains to be seen how changes in factors such as staffing, COVID-19, technology, and reimbursement will affect their future.

Easing the pain of electronic health records

By Cynthia Saver

Aaron Zachary Hettinger, MD, MS

Aaron Zachary Hettinger, MD, MS

Electronic health records (EHRs) have been decried as a drag on an organization’s efficiency and a source of frustration for clinicians and managers. Complaints related to documentation time, compatibility with other systems, and report generation are common.

These shortcomings were reflected in the 2022 OR Manager Salary/Career Survey. More than half of OR hospital leaders (254 out of 404) and more than three-quarters of ASC leaders (112 out of 144) responded to the question: “What are the continuing challenges of EHR documentation?” By far, the most common complaint was the time it took to document, with respondents often citing the amount of information required and a non-user-friendly interface as sources of the problem. Other critiques related to lack of interoperability and difficulties in obtaining reports.

But EHRs are here to stay, and that can be a good thing for clinicians, managers, and their organizations. The data found in EHRs can be used to better manage patient care at both the micro (individual) and macro (patient population) level. “These systems have a large amount of data that we as clinicians and healthcare systems can use to better understand what is going on with our patients,” says Aaron Zachary Hettinger, MD, MS, chief research information officer for the MedStar Health Research Institute in Washington DC. Dr Hettinger has conducted research related to EHR use.

EHRs will never provide the perfect user experience, but OR leaders can take steps to ease the pain while maximizing benefits. To help them do that, this series looks at how OR leaders can optimize the use of EHRs. It will provide an overview of EHR challenges and how managers can work with staff and their IT departments to overcome those challenges, while also focusing on interoperability, setting the stage for successful EHR use, and how OR managers can obtain reports from the EHR that support their leadership endeavors.

Technology can support staff, but it also can cause stress. A 2019 report from the National Academy of Medicine called clinician burnout a “major problems”; listed “inadequate technology usability” as a factor contributing to burnout; and called on health systems to “optimize the use of health information technologies to support clinicians in providing high-quality patient care.” The COVID-19 pandemic prompted higher burnout rates, and in May 2022, a US Surgeon General advisory on burnout outlined the seriousness of the issue. The advisory noted that technology needed to be “human-centered, interoperable, and equitable.”

EHR is perhaps the most visible type of technology for staff and managers. Unfortunately, it can create problems related to staffing, patient safety, and OR efficiency.

Staffing. A poor EHR can cause nurses to exit the organization. According to a 2022 report from KLAS Research, which focuses on healthcare IT, 30% of nurses who reported spending 5 or more hours doing “duplicative or unproductive” charting per week said they were “likely to leave” their organization in the next 2 years. And a 2021 study by Kutney-Lee and colleagues found that nurses who worked in hospitals with “poorer EHR usability” were more likely to experience burnout and be dissatisfied with their jobs than those working in hospitals where the EHR had better usability. This increased risk for burnout also was noted in a 2021 study by Melnick and colleagues, which found a strong association between how nurses perceived usability and burnout; for every point higher on the System Usability Scale (SUS), the likelihood of nurse burnout was 2% lower. (The SUS is a 10-question validated tool used to measure satisfaction.)

Patient safety. An ineffective EHR can pose a danger to patients. The Kutney-Lee study found that patients in hospitals with better EHR usability were less likely to die or be readmitted. A 2020 study by Classen and colleagues found wide variation in the safety performance of EHR systems in hospitals and concluded that systems meet “the most basic safety standards” less than 70% of the time. (The researchers used the Health IT Safety Measure Test, which evaluates EHRs through simulated medication orders that have previously either injured or killed patients; the intent is to evaluate how well the EHR identifies errors associated with potential patient harm.)

OR efficiency. The time it takes to document in an EHR and instances when the EHR is “down” can affect turnover time and overall OR efficiency. A 2019 study by Harrison and colleagues found that EHR downtimes of greater than 60 minutes in the OR resulted in a 10% increase in OR time and longer lengths of stay for patients, although it did not affect 30-day mortality. The increase in OR times could have a profound impact on perioperative services’ bottom line.

All these factors create an urgent need for OR leaders to address EHR-related challenges so they retain staff, keep patients safe, and maintain an acceptable bottom line.

Manufacturers who want to meet EHR certification requirements set by the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONCHIT) have to conduct usability testing, including measuring satisfaction, typically with the SUS. A score of 68 is an average benchmark, but a 2019 study by Gomes and Ratwani found that 26% of EHRs in 2015 fell below that average, and SUS scores decreased for 44% of vendors from 2014 to 2015.

These results confirm that more needs to be done to improve usability. OR leaders can start by listening to staff because the EHR end users are in the best position to improve its use. “Usually when staff are complaining about things taking too long or being too cumbersome, they’re right,” says Joni Padden, DNP, APRN-BC, CPHIMS, chief nursing information officer at Texas Health in Arlington, Texas.

Dr Hettinger says a feedback loop that promotes staff input pays off for leaders. “Staff appreciate being able to provide input, and if they can help solve a problem, they are more likely to report the next problem, which makes the system safer,” he says. Feedback also helps address the gap between work performed and work imagined. “There is sometimes a gap between what managers think is going on and what is actually happening,” he adds.

One way to promote listening is to have a staff committee dedicated to the EHR. Texas Health has a surgical services work group that includes frontline clinicians from all perioperative and procedural areas such as GI, endoscopy, cath lab, and interventional radiology. The work group, which meets every other month, provides feedback on planned changes and suggests ways for improving the system.

UCLA Health also relies heavily on work groups, such as a perioperative nursing work optimization group that includes frontline clinicians from all five surgical sites and two nurse experts: Lisa Harrison, MSN, RN-BC, clinical applications analyst for information services & solutions, part of UCLA Health Information Technology, and Michelle Robison, MSN, RN, AGCNS-BC, CNOR, perioperative CNS for UCLA Health. The work groups, which meet monthly and align with the organization’s shared governance, need to approve any proposed EHR changes, and provide suggestions for improvements.

Representation from the various areas ensures documentation meets specific needs. “The group discusses application and feasibility at each site,” Robison says. “Sometimes a change may not be appropriate for the eye institute, which has different documentation needs, so we don’t include it there.” The perioperative work group may approve changes at that level, or, depending on the scope, the proposed action also may be reviewed by other stakeholders.

Cleveland Clinic involves staff through its documentation excellence committee. Currently, the committee is focused on nursing documentation, according to Nelita Iuppa, DNP, MS, BSN, NEA-BC, RN-BC, FHIMSS, associate chief nursing officer in the office of nursing informatics. The committee is aligned with the 25X5 initiative, led by AMIA (American Medical Informatics Association). The goal of the initiative, started in 2020, is to reduce documentation burden for clinicians to 25% of the current state by 2025.

Committee members, who meet monthly, include representatives from legal, accreditation, nurse specialty groups (including the OR), informatics, quality and safety committee, IT, and nonlicensed caregivers such as unit secretaries, nursing aides, and technicians. “They often get left out,” Iuppa says of nonlicensed caregivers. “They are often asked to document in the system without effective analysis to identify workload efficiencies.”

The committee regularly reviews the EHR to ensure it is relevant to the needs of the patient and clinicians, including reducing documentation that is not needed. “We look at fields that aren’t relevant to clinical care and ask if the information can be automated or obtained from another system instead of manually inputted by essential clinical workforce staff,” Iuppa says.

Padden at Texas Health reminds managers who are implementing a new system to keep superusers engaged beyond implementation. “People have [superusers] when they go live, but after the system is up and running, they release them back into the wild,” she says. “We didn’t do that; we told them we had tagged their ears and would be calling on them in the next decade.”

Tiffany Kelley, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, recommends designating at least two superusers or subject matter experts in the OR to avoid the pressure of a single person who will not always be available. Kelley is the Frederick A. DeLuca Foundation Visiting Professor for Innovation & New Knowledge at UConn School of Nursing in Storrs, Connecticut. “You want to choose people who know how things operate in the OR and have at least a year of experience,” says Kelley, who also is founder and CEO of Nightingale Apps & iCare Nursing Solutions in Boston. Often there are staff interested in breaking into the IT field, so these positions create opportunities for them.

Both Texas Health and UCLA also have work groups of physician users who collaborate with IT to better meet their documentation needs. Cleveland Clinic sends a survey by the Arch Collaborative (KLAS survey) to providers each year to learn their opinions about the EHR design and documentation. The survey report provides detailed results that include comparisons of Cleveland Clinic to national benchmarks for similarly sized organizations. A work group meets to review the results. “We build working plans and strategy around how to address provider—and nursing—engagement and satisfaction with EHR documentation,” Iuppa says.

Feedback from staff should go beyond committee work. Dr Hettinger says staff should be encouraged to report near misses related to the EHR, so reports can be investigated and improvements made. Staff also need to know who to contact with any general EHR-related concerns. “Sometimes they don’t know where to share those,” he says. Yet this type of information can help avoid future safety issues.

“The vast majority of safety hazards that we see are because the system is so complex, and no one person can appreciate all the little dots that need to be connected to take good care of patients,” Dr Hettinger says. Finding and addressing hazards proactively will help keep patients safer.

Perhaps one of the most important contributions of staff input is that it promotes usability of the EHR.

Joni Padden, DNP, APRN-BC, CPHIMS

Joni Padden, DNP, APRN-BC, CPHIMS

Michelle Robison, MSN, RN, AGCNS-BC, CNOR

Michelle Robison, MSN, RN, AGCNS-BC, CNOR

Tiffany Kelley, PhD, MBA, RN-BC

Tiffany Kelley, PhD, MBA, RN-BC

Lisa Harrison, MSN, RN-BC

Lisa Harrison, MSN, RN-BC

Nelita Iuppa, DNP, MS, BSN, NEA-BC, RN-BC, FHIMSS

Nelita Iuppa, DNP, MS, BSN, NEA-BC, RN-BC, FHIMSS

John Glaser, PhD

John Glaser, PhD

Usability is at the heart of an EHR that supports clinicians, and optimal usability comes only when the EHR is integrated into staff workflow. “EHR design has to be very clean and succinct and follow staff workflow,” Padden says. It is important to consolidate steps when possible. For example, the EHR can list the steps for the surgical time out, but the user should only be required to check one box indicating the time out was completed, rather than having to click on each step of the process.

To encourage consistent improvement in integrating the EHR into the workflow, anyone in perioperative services at UCLA can make an optimization request. “When we get a new request for documentation, we ask how we can put this into the system in a way that fits with the nurse’s workflow so it won’t be a burden,” Harrison says.

Robison adds that she and Harrison also listen to what staff believe is taking too much documentation time, and they research options for change. “We look at if there is a way to simplify or combine processes by bundling things,” she says. For example, when setting up the documentation for a medical chaperone, IT built hyperlinks to the policy and an education pamphlet into the documentation area, so they were readily available when needed. “Staff don’t have to search another web page; the information is right there,” Robison says.

Harrison says small changes—such as being able to delete a few keystrokes for one type of entry—can add up. “Even if it’s only an extra one or two steps throughout the day, when you’re doing multiple cases and seeing multiple patients, those extra steps are a cognitive burden on nurses,” she says. “When you take those extra steps away, it helps to decrease that burden.” Harrison and Robison applied the bundle and keystroke reduction principles to the fire safety time out: Nurses click one box to say it was done, but the whole procedure is available for access.

Standardization is another way to ensure optimal workflow. “The worst thing you can do is customize things that could be standardized,” Cleveland Clinic’s Iuppa says. “Everyone should be documenting in the same way.” Standardization improves efficiency for staff going from facility to facility or even case to case, although some customization may be needed for a specialty. Even when customization occurs, however, those in the specialty need to use the tools consistently.

Iuppa also advises watching for documentation that is no longer needed. For example, someone may have wanted to obtain a piece of data, but that data is no longer needed because of a policy change. “Regularly review policies and procedures to see what has been changed and what documentation can be taken out,” she says.

Removing items from the EHR can be challenging, so Iuppa says those on the EHR team, in collaboration with their clinical colleagues, need to be good gatekeepers when a request for an addition is made. “They should ask if it’s really essential to start documenting this,” she says. “We want to decrease caregiver burden and improve the clinician’s experience of working with the system.”

John Glaser, PhD, a lecturer at Wharton who previously held executive positions at Cerner and Siemens, agrees, noting, “There is the tyranny of large numbers of good ideas.” A variety of people might suggest additions to the EHR, and while each piece of information might be useful, in the aggregate they are overwhelming. There is also the question of what will be done with the information. Will the nurse or another clinician be able to follow up on a particular issue? “You want to ask, do we really need this? And if so, should someone else be getting it?” says Glaser, who was chief information officer at Partners Healthcare and a senior advisor to the ONCHIT.

Clinician satisfaction with the EHR has been linked to how the system was implemented. The 2022 KLAS study found that satisfaction varied from one organization to another, even when the same type of EHR was in use. The reason for the difference? How the system was implemented. “In one case, the clinical staff drove the change process, and in the other, they were victims of the process,” Glaser says. “In one case, there was really good training and they were able to personalize the systems to reflect their practice, and in the other they were pushed into a mold or cookie cutter.” Taking care—and time—to implement a system in a positive way will pay off with satisfied staff.

Education is part of implementing a new system, and most organizations integrate the EHR into orientation. However, ongoing education is important, too. Updates not only keep staff informed of changes, but also can be used to foster good documentation habits. For example, although staff may be tempted to fill in parts of the EHR before a case to save time, Robison at UCLA says, “I tell staff and students not to pre-document, but to document in real time.” Pre-documentation can lead to errors when staff fail to correct previously entered information to reflect a change, such as not using an implant that had been entered into the system.

Iuppa at Cleveland Clinic also advocates for real-time documentation. “The more time people batch or wait until the end of the case, the harder it becomes because things back up and distractions, changes in the patient condition, and interruptions to the flow of the day frequently happen,” she says.

Education also should include being transparent about the trade-offs of an EHR. Glaser cites a prescription as an example. When paper was used, it took only a few seconds to write a prescription, but when the clinician has to log in, identify the patient, and go through other steps, it takes longer. “It’s safer and more accurate, but there is a price to be paid,” he says. Organizations should say, “We’re going to ask you to do a little extra work for the greater good—quality and safety.”

OR staff and leaders also need to develop basic competency in technology. “You can’t rely on IT to fully understand your world and translate that into an effective EHR,” Iuppa says.

“Sometimes nurses are a little intimidated by technology, but that can be overcome,” Kelley adds. Although OR leaders do not need to understand in detail how an EHR is built, they can take time to envision what is needed to support clinicians in achieving goals, such as great quality. “Your ideas will matter because you will help other people see what’s needed; it’s a team approach,” Kelley says.

That approach depends on a strong manager-IT partnership.

A key task for managers and staff who want to optimize the EHR is creating a partnership with IT. “Developing that partnership helps you when you need to implement something or want to make improvements,” Harrison says. “You have a shared vision, which helps rally the troops.”

Iuppa notes that collaborating with IT promotes “usable systems that are intelligent and that are enjoyable to use.” In a strong partnership, IT shares their priorities and their limitations, which promotes mutual understanding. “You can have more of an intelligent dialogue versus being frustrated that you want something customized and can’t get it because it will cost too much money,” she says.

Building a relationship with IT may start with simply inviting staff to meetings or having a one-on-one meeting, says Kelley. She says OR managers might open the door by saying something like, “I’m trying to better understand how to use the data in the EHR. Can you help me understand how we can work together to do that?”

When working with IT staff, Padden at Texas Health says it is best to describe the problem that needs solving, rather than asking for a specific solution. “You want to let IT use their creative juices to help you solve it,” she says. For example, a manager might request a best practice alert, but further analysis reveals that it is a matter of needing to document data in a different way. A manager might then request a flow sheet, but the IT staff could recommend a smart form instead.

“A smart form is like a flow sheet, but it has a lot more functionality to it,” Padden says. When users answer items in a smart form, it can adapt to the response entered, so the user does not have to go through unnecessary steps. In addition, one-line reminders can be embedded, rather than flashing an alert. “The more best practice alerts you fire, the more staff will ignore them,” Padden says. “You can guide them down the correct path without having to throw alerts at them all the time” (sidebar, Managing alerts). IT staff also can consider how items such as order sets are displayed on the screen to make it easier for staff to complete documentation.

Kelley says that IT staff strive to design a solution to meet the needs of clinicians and their workflow. When someone requests a form be digitized, IT staff first ask questions to understand how the form is being used and completed. For example, staff may fill out part of a paper form, put it in their pocket, and finish it later, something that is harder to do with an EHR. “You can’t fold a computer,” Kelley says. She also points out that asking staff how they complete a form and watching them do it are two different things. “They may not be aware of some of the steps they do,” she says. “It takes time to shadow them, but it’s more effective.” Otherwise, a redesign may be needed after the new form is implemented in the EHR. “You need to break the assumption that you’re just replicating something on paper and expecting it to work as it did before,” Kelley says. “You’re going from a static framework to something that is dynamic.”

IT also can help managers and work groups investigate sources of documentation time. “The vendor usually has a tool you can use to analyze how long someone spends on certain sections,” UCLA’s Harrison says. The team can then focus on sections that take longer to complete, asking questions such as: “What is truly necessary to document and what is not?” and “Can what is documented be streamlined?”

On the OR side, OR leaders need to keep IT informed. “When you come up with new policies or practices, they need to know,” Iuppa says. She recommends regular meetings. “This helps both sides to keep their fingers on the pulse of what’s happening in each other’s world and how to optimize the IT side and the clinical experience side,” she says. These regular touch points help ensure OR leaders are aware of upgrades and changes and that they have a voice in features that are planned to be deployed.

“IT is your friend,” Padden sums up. An optimal EHR can be a positive force in the OR as long as leaders ensure that staff are heard. “If technology is not adapted to their workflow, nurses will feel frustrated which will have implications on care delivery,” Kelley says. “Make sure the focus is on the clinician and what they need, and then build the technology to support that.”

Electronic health records (EHRs) can be a force for good, promoting patient safety, but they also often have multiple pain points. OR leaders can take steps to ease those pain points.

After providing an overview of EHR challenges and how managers can work with staff and their IT departments to overcome those challenges, the focus will turns to interoperability, setting the stage for successful EHR use, and how OR managers can obtain reports from the EHR that support their leadership endeavors.

“The most important thing you can do is get involved as early as possible in the process and stay involved,” says Nelita Iuppa, DNP, MS, BSN, NEA-BC, RN-BC, FHIMSS, associate chief nursing officer in the office of nursing informatics at Cleveland Clinic.

Leaders need to understand that many factors go into selecting an EHR system. “EHRs have gone far beyond documentation of care into this whole ecosystem,” says Tiffany Kelley, PhD, MBA, RN-BC, the Frederick A. DeLuca Foundation Visiting Professor for Innovation & New Knowledge at UConn School of Nursing in Storrs, Connecticut. “It is a record of the patient’s experience with the organization as a whole, it is a data repository, it is a scheduling system, it is a billing system, and it is a documentation system.” Factors to consider when making an initial purchase or changing to another system include usability (have staff test the system), fees for requested changes, types of reports that can be obtained, and how the company handles upgrades.

In addition to the initial purchase, OR leaders should have a method for evaluating the system on an ongoing basis. “People think that you implement the EHR once, and then you never have to talk about it again,” says Kelley, who also is founder and CEO of Nightingale Apps & iCare Nursing Solutions in Boston, Massachusetts. “It’s a moving target because your needs change, and the system needs to be updated to reflect those changes.” As noted, staff committees can play an important role in this ongoing evaluation.

Iuppa suggests OR leaders become champions of the chosen system to the extent possible. “Use your understanding of organizational processes and make sure you intimately understand your clinical practices so that you translate that into how the system needs to work best for you.”

A system cannot talk to an OR leader, but a clinical informaticist, who combines clinical and technology expertise, can. “They are the specialists who can help advocate for you, the clinical leader, to make sure your needs are being translated into whatever system is being selected, and the design and overall experience of it,” Iuppa says.

Nurse informaticists are playing an increasing role in bridging the gap between clinical and IT staff. “They understand the needs on the clinical side and the capabilities on the IT side, so they can help formulate a solution that will meet the clinical needs,” Kelley says. “The discussion should always be driven by the clinical needs and how the system can be leveraged to support those needs.”

Essentially, nurse informaticists can serve as consultants to OR managers, helping them obtain the information they need to make the best care decisions. OR managers in smaller organizations that do not have a nurse informaticist on staff might consider contracting with one for a specific project or for a certain number of hours each month. “Many times, these projects can be done remotely, and you can accomplish your goal without building a full department,” Kelley says. Nurse informaticists can obtain board certification in their field.

Interoperability, which refers to the exchange of information across systems without special effort by the user, has multiple layers, Kelley says. “While there is some interoperability within IT systems, healthcare organizational systems, and between states, there remains a great deal more to be done in this area,” she says. “Fortunately, this is something that is a current focus at the national level.”

Interoperability is a complex issue. “The OR is a dynamic environment,” says Aaron Zachary Hettinger, MD, MS, chief research information officer for the MedStar Health Research Institute in Washington, DC. “You have the EHR and you have scheduling and billing systems you want to connect in a workspace with multiple people with differing needs.” Dr Hettinger, who has conducted research related to use of EHRs, notes that the goal is to make it easier for people to obtain the information they need. For example, clinicians in the OR who are completing safety checklists need to be able to easily review items such as previous images, consent documentation, and allergies.

At the organizational level, testing ahead of time is needed when adding systems, says Joni Padden, DNP, APRN-BC, CPHIMS, chief nursing information officer at Texas Health in Arlington, Texas. For example, the EHR documentation system is from a different vendor from the imaging system, so testing had to be done to ensure clinicians could view the images properly.

“Organizations should have strategic discussions about interoperability,” Iuppa at Cleveland Clinic says. Those discussions should include future plans by year. “There will always be new technology and equipment coming in, so you not only need to have a purchasing plan, but a road map for integration,” she says. Planning for integration enables leaders to make the business case for interoperability. Return on investment, for example, might include saving time or more accurate billing. Planning also must include priorities. “It’s really important for an organization to have transparency as to what their long-term goals are so they can make those decisions as to what to prioritize in the interoperability space,” Iuppa says. “This is especially important as we are designing new models of care to meet the ever-changing demands on the healthcare workforce.”

At the same time, clinicians, leaders, and organizations need to be realistic. “People think everything should be connected to everything else,” says John Glaser, PhD, a lecturer at Wharton who previously held executive positions at Cerner and Siemens. “That’s never going to happen.” He points out that this type of seamless connection has not occurred in any other industry, so it is unlikely to occur in healthcare.

Glaser is a former senior advisor to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology and a member of the advisory council for Health Level Seven International (HL7), a nonprofit organization dedicated to facilitating the integration of electronic health information to support clinicians. The organization includes healthcare providers, government stakeholders, payers, pharmaceutical companies, vendors, and consulting firms.

Part of the reason full interoperability will not occur is that companies want to limit what competitors have access to. However, Glaser says the healthcare field can take some interoperability lessons from the banking industry. We can use our credit cards and cash checks nearly everywhere in the world because banks are willing to move money from point A to point B as part of what is called a “settle up.” On the other hand, banks do not have access to one another’s individual accounts because they do not want other banks to target potential clients who have a lot of funds. “Banks focus on a few key transactions for which there is a clear case for everyone to be involved,” Glaser says.

Those types of areas in healthcare might be pre-authorization or external lab results available in the EHR. Creating interoperability in these areas will depend on industry representatives working together. One model for this is OpenTravel, an alliance of travel companies that focuses on facilitating communication among companies in the global travel industry—air, hotel, car rental, and supporting software companies.

“Interoperability is a shared responsibility,” Dr Hettinger says. He notes that vendors want to sell a safe and efficient product that helps their bottom line and their company’s reputation. However, vendors do not know the many nuances of different healthcare systems. Clinicians on the frontline know what the issues are, but do not know what can be changed. Only dialogue among clinicians, organizations, and vendors can lead to interoperability

How can OR leaders best leverage the data in an EHR? “The fundamental question is, how can the data better inform your decision?” says Kelley. “What do you need to know to make a particular decision?”

Answering that question requires having a conversation with the nurse informaticist or another IT analyst who listens to what challenges the leader is trying to address, such as staffing or turnover. The two can then determine what data would be helpful in addressing the challenge. IT will know if that data can be obtained from the EHR and presented in a report. “There are thousands of fields, so picking the right field is just as important as knowing what data you want,” Kelley says. If the data are not there, the IT staff can help determine the best way to obtain it. “It’s not just asking for a report,” she adds. “It’s walking through the process and understanding each and every step.”

When considering reports, Texas Health’s Padden advises focusing on a specific topic: “We see people struggle when they try to incorporate too many things into one report.” Managers tire of reviewing lengthy reports and quit using them. “Having shorter, easier reports is better than one long one,” she says.

Managers typically use two types of EHR-related reports: those that have been set up and run automatically and those that managers set up and run as needed, usually to examine longitudinal trends (sidebar, “Types of reports”). For example, a report might pull all patients scheduled for a total knee to ensure that planned implants are available.

Padden notes that reports should match the needs of the person receiving the report. For instance, a charge nurse who is running the OR board may need a real-time report on room status, but the manager of orthopedic services may need to know the number of implants in the past 6 months and trends in which surgeons are using which implants.

Iuppa says that capacity planning is an important use of real-time data. “PACU managers can forecast what kind of care a patient is going to need postoperatively, so they can better align resources,” she says. Knowing factors such as blood loss, medication infusions, and number of wounds can help determine if a patient will be best served in the PACU or in a critical care unit, and how much one-on-one care will be needed.

Padden notes that a key factor in gaining useful reports is to ensure the contract with the EHR vendor specifically states that the organization owns the data. “You have to be able to access the data whenever you want,” she says. Managers should be wary of vendors who agree that an organization owns the data, but then require managers to access it only through reports in the vendors’ systems. “It has to go into your data warehouse so you can do with it what you need to do and not simply have them send you a PDF of a report,” she says. “That doesn’t work.”

Padden adds that many leaders, particularly mid-level ones, may struggle with data analysis because they tend to focus on where something is documented, such as a flow sheet, rather than reviewing a full report. “You have to get really good at looking at reports,” she says. Those include spreadsheets and graphic representations of trends.

“The better managers get at understanding the powerful tools of reports and how to get them, the happier and the more productive they will be as managers,” Padden says.

Many EHR changes can be made at the organizational level, but not all. When asking an EHR vendor to make a system change, Iuppa says it is important to understand that the vendor has limited resources and constraints, just as the organization does. “What we often don’t understand when we’re requesting changes is that sometimes it takes time to design a solution, code it, and evaluate it to make sure it’s compliant with other requirements for the design,” she says.

One tactic for change is for organizations to partner with others using the same EHR to gain greater leverage for a request. User groups are a valuable resource because those in the group will have similar challenges and goals. Multiple organizations can then approach the vendor with the same request. “The more you can show that it’s a problem not just for you but for many people, the more likely they are to hear you and to prioritize your request among the thousands they receive every day,” Iuppa says. “It’s harder to say ‘I want this one-off niche solution for my organization.’” Those types of solutions create a problem for vendors in the case of upgrades that might have to then be adapted for one organization.

Dr Hettinger points out that some changes are more difficult than others because many organizations are now working with systems that have been in place for years. “Some think about the EHR as this tool that gets implemented almost like a smart phone where you go to the store and buy a smart phone and everything is set up for you,” he says. “But the reality is that it’s very much a configuration among the vendors, the healthcare systems that are implementing it, and the staff members who are using it.” Decisions made years ago were made by those with the best of intentions and with the best available information at the time. Now that EHRs have become embedded into systems, organizations—and staff—are finding that the original configuration is not optimal.