Nurses have the highest incidence of work-related musculoskeletal injuries in the US, and OR nurses have the highest incidence among all nursing specialties.

Estimates in the literature say more than 50% report chronic back pain, and 10% must leave their profession entirely because of back injuries. It is also estimated that 90% of nurses will report musculoskeletal injuries in their careers.

“This isn’t surprising because nurses carry out an array of high-risk tasks in their daily practice,” says Christina Garbarino, BSN, RN, perioperative nursing professional development specialist, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Years of repetitive high-risk tasks, such as lifting and repositioning patients, lifting heavy instrument trays and supplies, and moving heavy equipment account for the vast majority of injuries.

The key word, says Garbarino, is repetitive because the injuries are cumulative over time, and they build upon each other and magnify. “What’s really troubling about these injuries is that they are often silent,” she says. “You reposition a patient and feel an ache in your back, but you continue on with your work that day. You have the next day off, and your back feels better. You go to work the next day after that, and the pain is subtle, and by the end of the day, it’s gone.”

Even though the pain disappeared, that does not mean the injury did not happen, says Garbarino, and such injuries accumulate over time. Musculoskeletal disorders can result in a decrease in job efficiency, job satisfaction, and quality of life. More serious ramifications are chronic pain and career-ending disability.

Even more concerning is that current nursing curricula do not have adequate education programs on how to prevent musculoskeletal injuries, she says.

A personal injury sustained by Garbarino when transferring a patient from the OR table to a stretcher, a rise in musculoskeletal injuries in the perioperative setting, and an increase in new OR staff who had not been educated on musculoskeletal injuries spurred Garbarino and her colleagues in the perioperative unit council to take action and start an education program on musculoskeletal injury risks and prevention.

They presented their idea to the nursing leadership team members in perioperative services, who were “extremely supportive,” she says, and they sought the support of staff members, who also were supportive.

Next, they formed a core team that included Taneka Curtis, MHA, BSN, RN, CNOR, the nursing leadership representative; three frontline nurses, including Garbarino; an injury prevention specialist from the health system; and the perioperative nursing educator. Garbarino says the frontline nurses were invaluable because ergonomic challenges are part of their daily lives.

The team began with a literature review, which proved invaluable in their journey, and then identified their areas of focus. An important finding from the literature review was that the number of articles related to ergonomics in the OR had grown each year.

Results from the review showed that a lack of knowledge in ergonomic principles, practices, and risks led to an increase in injury. They also showed that when an increase in knowledge was made possible by a strong educational program, overall injuries decreased, time off work decreased, and staff were more satisfied with their jobs.

Results from the review showed that a lack of knowledge in ergonomic principles, practices, and risks led to an increase in injury. They also showed that when an increase in knowledge was made possible by a strong educational program, overall injuries decreased, time off work decreased, and staff were more satisfied with their jobs.

The literature further recommended that ergonomic training sessions be held at least yearly or in mini sessions throughout the year.

Another important finding was the impact that work-related musculoskeletal disorders and injuries had on staffing, accounting for one third of sick leave. In addition, 12% of nurses were leaving the profession yearly, and 70% of the time, one reason nurses chose to leave the profession for good was because of work-related musculoskeletal injuries.

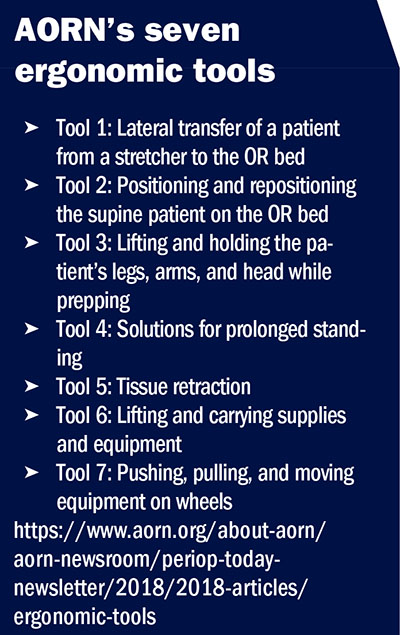

In addition, the team learned of AORN’s seven ergonomic tools and articles on how to implement the tools, which cover high-risk tasks in the OR and algorithms for safely and appropriately carrying out these tasks and mitigating the risks (sidebar, AORN’s seven ergonomic tools).

Garbarino notes that one major finding from their literature review that became the “bones” of their project and gave it structure was the Cairo University Hospital study on occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders and improving ergonomics among OR nurses.

She says they used the Cairo study as an inspiration for their design. It included many of the outcomes they were striving for and an educational program. The Cairo group saw a substantial decrease in ergonomic injuries and staff sick leaves.

They modeled their project after the four-part structure of the Cairo study:

• Part A: Pre-education phase—includes a pre-evaluation questionnaire with demographic material, a quiz, and pre-observations in the OR. This phase involved two monthly early morning team meetings and conversations with staff members about the challenges they were facing and what they wanted to see come out of the program.

• Part B: Education phase—includes closely working with an injury prevention specialist to produce an educational video and presentation for staff. The Cairo study did not include a video.

• Part C: Post-test phase—includes post-observations in the OR and a test that had the same questions as the quiz in Part A but with different demographic questions. “We wanted to know how the staff felt about the education we presented to them and whether they felt better prepared to undertake ergonomic tasks,” she says.

• Part D: Education phase for the future—includes education for all new staff and yearly education on ergonomic practices for all OR staff. Garbarino adds that they are hoping to expand the education sessions to staff in other areas of the hospital who move patients, move supplies, and move equipment.

The team created their quizzes using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). REDCap is a web-based application developed by Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, which can be used to create surveys and quizzes that can be sent out online. REDCap is free for nonprofit organizations and is HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) compliant. As more people take the quiz, that data updates in real time.

A total of 124 staff members took the initial pre-education quiz, for a participation rate of 83%. The average quiz score was 68%, which Garbarino says the ergonomics taskforce knew they would be able to improve with education.

“We set out goals early on and we stuck to them,” Garbarino says. The ergonomics taskforce’s short-term goals were to:

• decrease the incidence of staff injuries in the OR setting

• decrease absences due to work related injuries

• increase staff knowledge with educational classes

• increase staff perceptions of safety and preparedness when performing ergonomic tasks.

Their long-term goals were to:

• provide education for new staff members and yearly education for existing staff

• lower the cumulative effects of work-related injuries over time

• conduct regular audits to ensure safe practices became ingrained in the culture

• get feedback from staff members on the success of the safety practices and project.

“Having the staff’s perspective was extremely important to us,” says Garbarino. “We wanted this to be something that worked for the staff and kept them safe. We based a lot of our training on staff feedback gleaned from questions we asked them.”

Among the questions were:

• “What do you need for ergonomic training?”

• “What are we lacking?”

• “What can we offer you?”

• “What do you want to see more of?”

• “What are your ergonomic challenges when carrying out high-risk tasks?”

• “What would you like to see in your education sessions?”

Garbarino says they got many of the same responses from staff, but, overwhelmingly, they wanted a video of the safety practices being performed. The AORN seven ergonomic tools were invaluable in writing the script for the video, she says, as well as for writing the quizzes.

“COVID-19 hit us mid-project and presented us with a huge challenge,” says Taneka Curtis, MHA, BSN, RN, CNOR, nurse manager at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Elective cases had stopped, and staff were not readily available.

“Our unsung hero was our timeline,” says Garbarino. “We didn’t realize when we created it how essential it would be, but having a strong, detailed timeline helped the team stay connected and stay on task” (sidebar, Ergonomics’s Taskforce Project Timeline).

The timeline had specific tasks that had to be completed each month. It had to be revised many times, but because the timeline contained all of the key elements, it was easy to change, says Garbarino.

“We stayed true to the timeline and our process,” adds Curtis, “and by June of 2020, we were back to a full schedule. This allowed us to return to our observations, but there was still the challenge of how to meet as a team because of social distancing.”

The team decided to develop their video script in an online Microsoft program that all of the team members could access and edit without being in the same room. The script also had an audio column that could be matched to the video column.

“In the end,” says Curtis, “the Microsoft program proved to be our friend.”

An internal service at Penn Medicine was used to film the video. To gain support for the video, they wrote a proposal to the perioperative executive committee citing the data they had collected on staff injuries and the leaves of absences and days off that resulted from those injuries. They pointed out that the estimated costs of the injuries were far greater than the cost to film the video.

With the support of the executive committee, the ergonomics taskforce succeeded in making the video, which is about 25 minutes long. The video was integrated with the educational phase, which consisted of in-services for the staff.

Scores on the post-education quiz went up from 68% to 94%, and all participants believed that the education was effective and that they would be more likely to advocate for and use proper body mechanics in their practices as a result.

Garbarino notes that they did some post-test observations, which showed improvement in the lateral transfer of patients, lifting heavy supplies, and repositioning patients. Issues that decreased but were still prevalent, and may be revisited in future education sessions, are standing in a static position or awkward position, as well as assuming awkward postures with the neck flexed for prolonged periods of time.

“In the future,” says Curtis, “we have several plans.” These are:

• Have a yearly in-service—“We want to continue to provide education for the staff on how to move well, and we want to decrease their injuries and increase their work time,” she says. “Staffing is a big challenge currently, and a number of sick calls and leaves of absence could further jeopardize us.”

• Continue to work with the employee injury prevention department—“Our injury prevention specialist was a part of our team, and we are going to continue to work with her to advance our project throughout the system,” says Curtis.

• Become a part of new-to-practice education for nursing and ancillary staff—“This is key to making the work environment safe for all perioperative teams, not just nursing, and to take care of our patients directly and indirectly,” she says.

• Have regular audits—“We are going to continue with regular audits to ensure our education has had an impact on the staff,” says Curtis.

• Health system expansion—“We want to expand the program throughout the health system,” she says.

“Our goal is to share what we have done and help all employees learn how to Move Well.”

—Judith M. Mathias, MA, BS, RN, is the clinical editor of OR Manager. Previously, she was clinical editor of the AORN Journal and a cardiac surgical nurse at Rose Medical Center, Denver, and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Abodollahi T, Razi S P, Pahlevan D. Effect of an ergonomics educational program on musculoskeletal disorders in nursing staff working in the operating room: A quasi-randomized controlled clinical trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(19):7333.

AORN ergonomic tools: List of implementation articles. AORN. Accessed February 2022.

Ata G, Khalifa E M, Desouky S E, et al. Occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal disorders, Cairo University Hospital study on improving ergonomics among operating room nurses at Cairo University Hospitals. British Journal of Medical and Health Research. 2016;14(9):1-11.

Burdorf A, Jansen J P. Predicting the long term course of low back pain and its consequences for sickness absence and associated work disability. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2006;63(8):522-529.

Curtis T, Garbarino C. Move Well—Targeting education teaches staff how to avoid musculoskeletal injuries. OR Manager Conference. 2021.

Ou Y K, Liu Y, Chang Y P, et al. Relationship between musculoskeletal disorders and work performance of nursing staff: A comparison of hospital nursing departments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(13):7085.

Reed L F, Battistutta D, Young J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for foot and ankle musculoskeletal disorders experienced by nurses. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014;15:196.

Richardon A, McNoe B, Derrett S, et al. Interventions to prevent and reduce the impact of musculoskeletal injuries among nurses: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2018;82:58-67.

Smedley J, Egger P, Cooper C, et al. Manual handling activities and risk of low back pain in nurses. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 1995;52(3):160-163.

Yassi A, Lockhart K. Work-relatedness of low back pain in nursing personnel: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;19(3):223-244.