Editor’s Note: For more recent data on obstructive sleep apnea care, risk factors, and resources, see the article, “Blast from the past: Revised data, evolving standards for OSA care in the perioperative setting,” published in July 2025.

An estimated 22 million people in the US have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), but up to 80% of cases are undiagnosed, and some 30% to 40% of the surgical population has diagnosed or suspected sleep apnea.

More than 3 years ago, The Joint Commission issued a Quick Safety document about the potential risks for perioperative complications in patients with OSA. Among its recommendations was: “Consider adding sleep pattern questions as part of a nursing assessment upon inpatient admissions and during surgical reviews.”

Yet results of a 2018 survey of 1,222 perianesthesia nurses by Erwin et al suggests that practices are still inconsistent when it comes to screening and management of surgical patients with OSA.

OSA is characterized by partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep. Untreated, it can lead to comorbidities including apnea, hypoxemia, hypertension, heart disease, cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, stroke, and sudden death.

The American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses (ASPAN) recommends that all surgical facilities have policies for managing OSA, but not all of them do. In fact, only 36% of respondents to the survey by Erwin et al. said they “strongly agree or agree” with the statement that their facility uses an efficient and policy-driven perioperative process for diagnosing patients suspected of having OSA.

Less than half of respondents said that they discuss preoperative screenings with the attending anesthesiologist. Just 20% said patients at risk for OSA are referred for additional testing, and less than half (46%) said these at-risk patients are told to follow up with their general or internal medicine practitioner.

Yet the authors cite a study showing that educating perioperative nurses and getting them to use the STOP-Bang questionnaire for preoperative assessment led to a 16% improvement in identifying OSA.

Newly updated guidelines from the Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine provide evidence-based recommendations for the intraoperative management of patients with OSA—notably in the areas of airway management, commonly used anesthesia-related drugs and agents, and anesthetic techniques.

Organizations that aren’t currently assessing patients for OSA might want to take a page from a small rural facility that has implemented a screening and management program. As someone with previously undiagnosed OSA himself, Charles Burnley, MSN, RN, director of surgical services at Sauk Prairie Healthcare in Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin, has a keen interest in serving the needs of this patient population. By leading the team charged with this initiative, Burnley has helped improve patient care and the bottom line.

Sauk Prairie Healthcare is a 36-bed not-for-profit acute care hospital and Level 3 trauma center. This rural facility collaborates with larger facilities in the area for certain services, but for OSA diagnosis and management, there wasn’t anything readily adaptable.

Sauk Prairie leaders created a task force to assess the tools and equipment that would be needed. They were able to justify adding sleep services, and they expanded screening to their primary care clinics. In addition, they generated revenue to compensate for the investment needed to launch the program.

In January 2016, Sauk Prairie formed an OSA workgroup to develop a charter and create a multidisciplinary team consisting of a surgeon, a certified registered nurse anesthetist, the chief nursing officer, nursing leaders and staff, a respiratory therapist, a physical therapist, and the nurse educator.

The charter identified the committee’s goal: to identify and use evidence-based data to deliver care specific to the operative OSA patient. The main steps in the process included:

• researching other hospital practices

• doing a literature review

• deciding on which assessment tool to use

• assessing the surgical population for occurrence rates

• preparing for patient OSA needs the day of surgery.

Working as co-team leaders, Burnley and Terry Zeuske, RN, provided team direction, set meetings and agendas, and kept the team focused. Burnley emphasized the need for team leaders to also be team members who are committed to attending, participating, and being champions of the project.

“Recently we transformed the way we control information operations as it relates to patient care,” Burnley explains. “For patient care and documentation, we have an information governance structure that includes a clinic group, a hospital group, and a provider medical technologies group. These groups are governed by the information governance committee, which keeps the senior leadership and board of directors involved in decision making at a very high level. It keeps everyone aligned with the strategic plan,” he says.

“We have five vice presidents and one chief executive officer,” adds Denise Cole-Ouzounian, MSN, APN, CNML, CCRN, vice president, patient care services, and chief nursing officer. “The clinical areas all tie up to the vice president of patient care services, so oversight for operating surgical services is under me.”

Cole-Ouzounian was the project champion, and because of her clinical background, she was able to provide important perspective and advocate for the funding needed for the project.

“I communicate with the senior leaders. None of them are clinical, so it’s important that they have a link to the clinical team,” she explains. Team members were educated about the project scope, boundaries, and objectives. In addition, she says, “we left our titles at the door,” she says—everyone was considered equally important to the project.

At the end of every meeting, team members reviewed what had been accomplished, what the next steps were, and who was responsible for what. That way, it was clear that specific tasks were expected to be completed by the time the group met again, she says.

At the end of every meeting, team members reviewed what had been accomplished, what the next steps were, and who was responsible for what. That way, it was clear that specific tasks were expected to be completed by the time the group met again, she says.

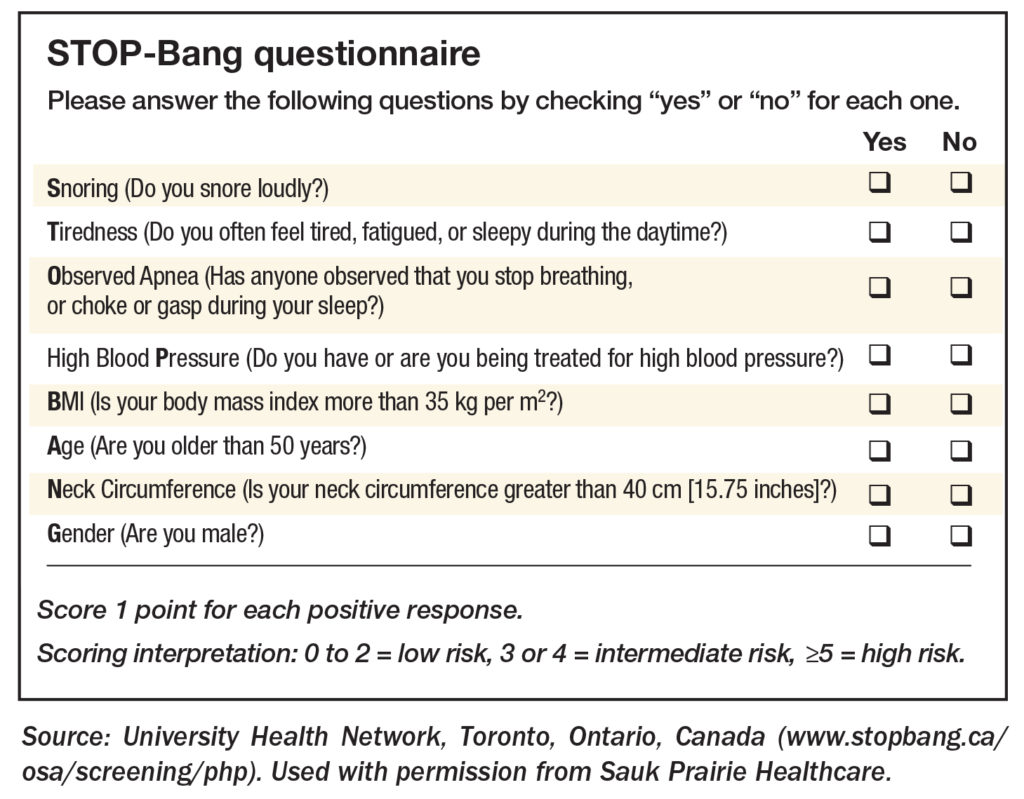

STOP-Bang, Berlin, Eppworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), and Stop were the tools the team evaluated based on accuracy in predicting OSA, ease of use, ease of implementation, cost, and current utilization. They chose the STOP-Bang questionnaire, swayed in part by a study in the British Journal of Anesthesia that found patients who tested positive on this screening tool were more likely to be diagnosed with moderate to severe OSA (sidebar at right).

“After we chose STOP-Bang, we performed an initial assessment of our surgical population and found 28.5% either had OSA or were at high risk for moderate to severe OSA,” Cole-Ouzounian says. “This is lower than the average (32%), but it’s still huge—prior to this, no one was being assessed or receiving treatment.”

STOP-Bang is owned by the University Health Network in Toronto, Canada, and must be purchased. At first, the price was too steep for Sauk Prairie, but after some negotiating, an affordable price point was reached.

“We also needed equipment,” Cole-Ouzounian says. “We worked with the surgery center nurses, and they collected data to see what was needed. We needed five additional Auto-CPAP [continuous positive airway pressure] units.”

Other steps included:

• creating an assessment and other documentation in the electronic medical record to support patient care

• creating an assessment and other documentation in the electronic medical record to support patient care

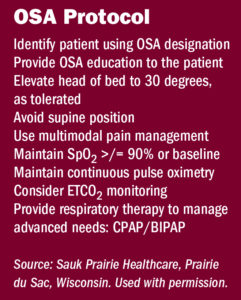

• creating a protocol for surgical OSA patients (sidebar at right)

• creating an order set and procedure for anesthesia providers

• agreeing upon a patient identifier

• creating a standardized discharge protocol and instructions

• developing a policy and getting approval from the Surgery & Anesthesia Committee.

The STOP-Bang assessment is captured within the electronic health record, Burnley says. “The assessment is within the preop checklist, making it nearly impossible to miss.”

The first screening assessment was implemented in the preoperative area in October 2017. As of the end of June 2018, a total of 3,985 surgical patients were screened, of which 94.9% had a preoperative assessment completion rate. Of those patients, 74.2% went on to need the OSA protocol, Cole-Ouzounian notes.

“They screened at a high rate, and those that screened at a high rate needed the order set: 26.7%. Of those who had the orders placed, 42 new postsurgical patients were required to spend the night using CPAP.”

The screening tool was rolled out to Sauk Prairie primary care clinics, which now complete OSA assessments for all physicals and all preoperative H&Ps. “We still receive patients outside of our primary care physician providers, and our presurgical nurses do the screening for those patients,” she explains.

“Sleep services is not just about doing a sleep study,” Cole-Ouzounian says. “You have different levels of patients such as a new patient or a returning patient with a level 1 to 5 service. You can provide sleep education with a sleep technician. You can provide initial CPAP prescriptions or refills. It’s important for patients to come in at least annually to have their equipment checked and make sure it’s being cleaned properly.”

Working with her director of respiratory therapy, Cole-Ouzounian developed a pro forma to present to senior leadership to justify the need for sleep services. “Sleep clinic startup costs include staff salary and benefits, and fees for the medical director, sleep study interpretation, and home sleep apnea testing interpretation, plus supplies and variable expenses. The total cost was $161,000,” she says. The facility had a medical assistant and a unit secretary who wanted more hours, so they were assigned to work with sleep services.

“We opened on April 1 with an advanced practice provider working three 12-hour days, and we have had 53 new referrals for sleep medicine from primary physician care clinics since April 2018,” Cole-Ouzounian says. “We saw 177 patients during this time, and each month it grows: 126 of the 177 were completely new to sleep services—they were already in our primary care network, but they had never had sleep services.”

Charges associated with the sleep clinic, which opened in April 2018, include:

• New patient visits range from level 1 to 5 (charge range, $145 to $685).

• Established patient visits range from level 1 to 5 (charge range, $86 to $475).

• In-lab sleep studies, ~ $5,500.

• Home sleep study, ~ $1,000.

The total startup costs were $161,000 vs the yearly revenue of approximately $378,000, which translates to a net gain of $217,000, Cole-Ouzounian says. “This was a very good program, not just for our patients and staff but also for our organization’s financial benefit. We improved patient outcomes. We improved provider awareness. None of our primary care physicians had been doing sleep apnea screening, and now they all do it.”

There’s also the potential for less litigation because fewer patients are at risk if they have a CPAP, she notes.

“This was a grass-roots initiative in which overall cost was small. In addition to the $161,000, we spent about $10,000 in salaries for people to go to meetings. They needed that protected time,” she adds. “But our outcomes are so much more than that: We have excellence in patient care. We have an organization and leadership that prioritize excellence in quality. Safety comes first. Sometimes you’ll need to sell this to your senior leadership team because they might not be clinical and they might not understand.” ✥

Denise Cole-Ouzounian, MS, APN, CNML, CCRN, is vice president of patient care services, and Charles Burnley, MSN, RN, is director of surgical services at Sauk Prairie Healthcare in Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin.

Burnley C, Cole-Ouzounian D. Can you hear me breathe? Investigating the suspect obstructive sleep apnea in the preoperative population. 2018 OR Manager Conference.

Erwin A M, Noble K, Marshall J, et al. Perianesthesia nurses’ survey of their knowledge and practice with obstructive sleep apnea. J Perianesth Nurs. Published online April 18, 2018.

Hauk L. Undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea in the perioperative patient. AORN J. 2018;108(4),P7-P9.

https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/23/quick_safety_issue_14_june_2015.pdf

Kaw R, Gali B, Collop N A. Perioperative care of patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Treatment Options in Neurol. 2011;13,496-507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11940-011-0138-5.

Lockhart E M, Willingham M D, Abdallah A B, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea screening and postoperative mortality in a large surgical cohort. Sleep Medicine. 2013;14,407-415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.018.

Memtsoudis S G, Cozowicz C, Nagappa M, et al. Society of Anesthesia and Sleep Medicine guideline on intraoperative management of adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Anesth Analges. 2018;127(4):967-987.

Shin C, Grabitz S, Timm F P, et al. Development and validation of a score for preoperative prediction of obstructive sleep apnea (SPOSA) and its perioperative outcomes. BMC Anesthesiol. 2017;17,1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-017-0361-z.

Spence D L, Han T, McGuire J, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and the adult perioperative patient. J PeriAnesthes. Nurs. 2015;30, 528-545. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1089947215001434.

Williams R, Williams M, Stanton M P, et al. Implementation of an obstructive sleep apnea screening program at an overseas military hospital. Am Assoc Nurse Anesth. 2017;85(1), 42-48. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4530/8079ae1fb9558b41b3b563bc684ef162078e.pdf.

Xara D, Mendonca J, Pereira H, et al. Adverse respiratory events after general anesthesia in patients at high risk of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Brazilian J Anesthesiol. 2015;65, 359-366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2014.02.008.