Many ingredients go into the recipe for patient safety, and culture is one ingredient that is often overlooked. If the

perioperative culture penalizes those who call out patient safety issues and doesn’t commit to continuous quality improvement (QI), it’s likely only a matter of time before a serious error occurs.

“When you have a culture where people are afraid to speak up, it impacts the safety of patients under your care,” says Gail Horvath, MSN, RN, CNOR, CRCST, senior patient safety analyst and consultant at ECRI in Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania.

Creating a culture of safety (COS) that facilitates ongoing improvement and encourages people to speak up can help avoid potential errors, reduce mortality, and save money.

A 2013 study at a children’s hospital found substantial reductions in serious safety event rate, preventable harm, cost, and hospital mortality associated with the implementation of a QI program intended to reduce preventable harm. “The researchers found that increased safety attitude scores corresponded with decreased serious safety events,” Horvath says.

In a 2016 study, 9 of 12 dimensions on the Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture were associated with lower colon surgical site infection (SSI) rates, including teamwork across units and supervisor/manager expectations and actions promoting safety.

These two studies were based in a single facility, but multicenter studies also have reported positive associations between a COS and patient safety. A 2019 study found that a higher percentage of positive Safety Attitudes Questionnaire responses was associated with lower postoperative morbidity (although not mortality) among 49 hospitals in a statewide QI collaborative.

And Horvath says that a classic 2010 study of 30 ICUs remains relevant today. For every 10% drop in patient safety scores, length of stay increased by 15%, and mortality increased by 24%. “I think that’s compelling evidence that culture does have an impact on patient outcomes,” she says.

Here are two examples of OR leaders who have successfully implemented a COS.

Bethany Pelikan, MSN, MBA, clinician educator at UPMC Shadyside in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, says that, compared with other hospital departments, the surgical services department was struggling with lower COS survey scores. Efforts to turn that around led to significant improvements from 2017 to 2019, with the OR exceeding the goal of 10% improvement for three targeted composite section scores: supervisor actions promoting safety (42% improvement), facility management support for safety (61% improvement), and feedback and communication about error (10.4% improvement). Overall, scores improved for 9 of the 10 total questions. Here’s how UPMC Shadyside did it.

Team. A team was formed that included OR physician leaders, directors, educators, and staff, as well as safety and improvement specialists. “We felt it was important to get surgeons, staff, and leaders involved so we could create a culture of safety,” Pelikan says.

The team used a fishbone diagram to identify factors in four areas that contributed to lower COS scores: leadership, communication, environment, and staff factors. Based on the team’s discussions, subgroups focused on three strategies: safety huddles, culture and safety meetings, and staff reporting and recognition. “As we worked on these, we tried to get as much feedback as we could from frontline staff,” Pelikan says.

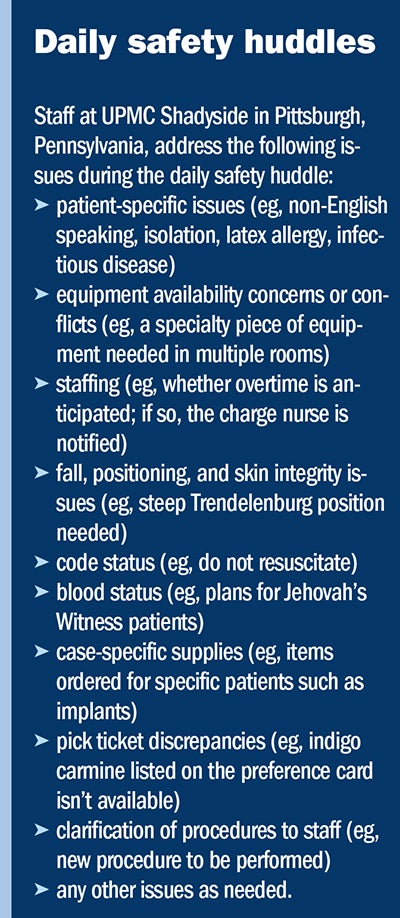

Daily safety huddles. Shadyside UPMC has 23 ORs and multiple specialties, so clinician leads in each service line met with those in that service each morning, rather than in a single department-wide safety huddle, Pelikan says. “We found a meeting location for each service, let the staff know what time they would be meeting, and determined what information needed to be covered to help ensure the safety of our patients,” she says (sidebar, “Daily safety huddles”). Having a specialty clinician lead each huddle encouraged staff engagement.

Daily safety huddles. Shadyside UPMC has 23 ORs and multiple specialties, so clinician leads in each service line met with those in that service each morning, rather than in a single department-wide safety huddle, Pelikan says. “We found a meeting location for each service, let the staff know what time they would be meeting, and determined what information needed to be covered to help ensure the safety of our patients,” she says (sidebar, “Daily safety huddles”). Having a specialty clinician lead each huddle encouraged staff engagement.

Culture and safety meetings. The team started quarterly interdisciplinary joint surgical services COS meetings that include OR staff, anesthesia providers, and surgeons. Pelikan credits the chiefs of surgery and anesthesiology for reinforcing the importance of physician attendance. Virtual meetings necessitated by COVID-19 increased attendance, although the number of meetings fell to two in 2020. This year, the team is returning to the quarterly schedule.

Initially, areas needing improvement were identified by a staff and physician survey and addressed by the appropriate person; for example, the chief of anesthesia would discuss an anesthesia-related safety issue. Now topics come from staff feedback and the management team.

Staff reporting and recognition.UPMC’s RiskMaster program provides a way for staff to “report any type of safety issue or concern, whether it’s for the patient, for yourself, or for a coworker,” Pelikan says. Reports are reviewed by the hospital’s risk management team; those related to the OR are then reviewed during the weekly meetings of the Surgical Services Oversight Committee.

Staff initially feared they would be punished for reporting, but allowing them to report anonymously has significantly increased the number of reports, Pelikan says. The ability to report from any hospital computer makes the process user-friendly.

In response to staff’s desire for feedback on what they report, Pelikan says, “we’re working on being more transparent to staff about how safety issues from the reports are being addressed.” However, sometimes human resources policies prevent a detailed response, and not all staff accept responsibility for reading communications. Periodic re-education about the program is important to encourage reporting.

Pelikan says that UPMC’s Good Catch program promotes staff recognition for identifying safety issues and encourages reporting. Each month, the patient safety department gives gift cards to four to five staff members, and every quarter, an overall winner receives another gift, such as a coffee mug. In addition, the patient safety department brings cookies to the winner’s department, hangs a recognition banner, and provides a write-up for the organization’s internal publication. OR staff have won the award, including a surgical technologist who recognized the potential for a retained surgical object.

In 2018, when Jessica Clark, DNP, RN, NE-BC, became executive director of surgical services at AdventHealth Daytona Beach in Florida, there was a need to change current practices in order to reduce SSIs. Strategies such as changing skin preparation and enlisting patients in SSI prevention depended on creating a COS and encouraging staff to be strong patient advocates.

Efforts to do so led to a drop in SSIs such as those related to abdominal hysterectomy and colon surgery, and there were no colon infections over a 32-month period.

Team. Clark worked closely with an interdisciplinary team of staff and leaders from preadmission testing, the preoperative area, the OR, and the ambulatory surgery unit. “We discussed the overall plan and what actions we needed to take,” Clark says. “Depending on which particular piece of the puzzle we were working on, we would then involve other groups.”

For example, strategies that involved surgeons were presented to the physician-led OR steering committee. “We would explain what we wanted to change, along with the evidence and data behind it, and ask for their support to move forward,” Clark says.

To gain staff support for changes, the OR manager focused on the need for improvement and evidence-based guidelines from AORN, Clark says. “Focusing on the ‘why’ is the best way to garner support from our team,” she notes. Staff were also asked to respond to the question, “How do we get better?” Leaders encouraged staff to generate ideas and to value continual improvement.

Based on the work of the team and OR staff, several initiatives were implemented.

Patient participation. Patients now play an active role in reducing SSIs. During preadmission testing, they receive education about prevention and a brochure that explains:

• what to do before surgery (eg, use CHG [chlorhexidine gluconate] soap the night before and morning of the procedure)

• what to do at the time of surgery (eg, speak up if someone tries to shave you with a razor)

• what to do after surgery (eg, make sure healthcare providers clean their hands before examining you, either with soap and water or an alcohol-based hand rub)

• the signs and symptoms of infection

• when to call your physician.

“We start the conversation even before they arrive the day of their procedure, and do discharge teaching on the back end,” Clark says.

Skin prep. Skin prep changes included solutions and clipping. Clark asked the company that provides AdventHealth’s skin prep products to assess the organization’s prepping practices, including technique, dry time, types of preps, and positioning towels around the prepped site. Information in the subsequent report, in addition to information found in the literature, was used to standardize prepping among physicians and staff. Those standards are now part of staff’s annual competencies and help to promote a COS.

The skin prep change was accomplished fairly easily, but that wasn’t the case for hair clipping. In addition to standardizing clipping areas for different types of procedures, Clark says, hair clipping shifted from the OR to the preoperative area, which is where it should be done based on the evidence in the literature. But staff new to clipping left some abrasions, which made surgeons question the change. Clark reinforced the evidence and began tracking the number of abrasions. “We were able to show that as the team became more comfortable with clipping, abrasions stopped,” she says. The example illustrates the need in a COS to stay focused on what’s best for the patient.

Sustaining change. As part of the COS, Clark says, SSI rates are tracked to help sustain the changes made. “For every surgical site infection we have, we do a deep dive with our infection prevention team,” she says. “It’s a good way for us to make sure we’re still doing all the things that we’re supposed to be doing.”

AdventHealth also has implemented the Learning and ENgagement System (LENS) by Safe & Reliable Healthcare. The electronic board allows real-time patient safety communication from teams to the leadership team. Staff can text a message from their cellphones, which is posted on the board where hospital leaders can be immediately tagged to address and resolve issues.

“It has helped us with our high reliability culture of safety so we can identify potential issues and get them resolved quickly,” Clark says. For example, a team member who noticed that two medications with similar names were stored next to each other sent a photo to LENS and noted the potential error. Subsequently, the locations were changed.

As is the case with so many perioperative initiatives, creating a COS starts with leaders. “They need to model the desired behavior, they need to be visible, and they need the right experience, temperament, and education to handle the modern-day surgical manager role,” Horvath says.

Clark notes that the journey to a COS that promotes transparency and safe, reliable care “takes persistent, consistent leadership, but as long as you partner with your team and your physicians, you can do it.”

Horvath, Clark, and Pelikan will share their expertise during the annual OR Manager Conference, October 20-22, in Chicago. For more information or to register, visit www.ormanager.com. ✥

Cynthia Saver, MS, RN, is president of CLS Development, Inc, Columbia, Maryland, which provides editorial services to healthcare publications.

Brilli R J, McClead Jr R E, Crandell W V, et al. A comprehensive patient safety program can significantly reduce preventable harm, associated costs, and hospital mortality. J Pediatr. 2013;163(6):1638-1645.

ECRI, Institute for Safe Medication Practices PSO. Deep Dive: Strategies for Surgical Patient Safety. Executive Brief. 2020.

Fan C J, Pawlik T M, Daniels T. Association of safety culture with surgical site infection outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(2):122-128.

Huang D T, Clermont G, Kong L et al. Intensive care unit safety culture and outcomes: A US multicenter study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22(3):151-161.

Odell D D, Quinn C M, Matulewicz R S, et al. Association between hospital safety culture and surgical outcomes in a statewide surgical quality improvement collaborative. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229(2):175-183.