Hospital-acquired pressure injuries (HAPIs) fall under the care management serious event category, and the literature suggests the incidence of a pressure injury following surgery or a procedure may contribute to more than half of all hospital-related skin injuries. Furthermore, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has defined numerous hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) as non-reimbursable.

At Metro Health—University of Michigan Health in Wyoming, Michigan, a 208-bed community hospital, nurses collaborated to implement an evidence-based skin injury prevention plan for patients throughout their course of care. This program, launched in July 2018, has led to the identification of every high-risk patient and a decrease in pressure injuries in the perioperative/procedural (PP) areas each month. No reportable pressure injuries have occurred since January 2019.

HAPIs became a primary hospital focus when a progressive care unit (PCU) clinical nurse leader (CNL) started noticing some serious patient complications related to HAPIs. She discovered there were no standard nursing practices for pressure injury prevention. Baseline data collected by a retrospective hospital-wide chart review revealed that patients were three times as likely to get a stage III or IV deep tissue injury or an unstageable pressure injury (all non-reimbursable per CMS criteria) when compared to similar hospitals.

Skin injury prevention became a focus for PP services when baseline data revealed that up to 66% of the hospital’s patients with HAPIs had undergone a procedure before being identified as at risk. The majority of these PP patients scored low risk on the hospital’s standard Braden Scale risk assessment tool.

An intraprofessional team was formed that included a physician champion; a critical care services clinical nurse specialist (CNS); a PCU CNL; inpatient nurse educators; quality, safety, and risk nurses; a wound care nurse practitioner; and a surgical services CNL representing all outpatient areas (cardiac catheter [cath] lab, interventional radiology [IR], endoscopy, and surgical services). The team was tasked with decreasing the prevalence of pressure injuries and improving patient outcomes.

Risk identification is the first step toward decreasing HAPIs, and PP areas were at an early disadvantage because the Braden Scale did not capture the unique intrinsic and extrinsic factors of the PP patient: type of anesthesia, core temperature, patient positioning, bed surface, devices, and procedure length.

PP patients are at higher risk because they go through three phases of care: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative. Each phase of care presents different risk factors that are associated with skin injury. To identify high-risk patients, we needed a validated risk assessment tool that addressed all three phases of surgical patient care.

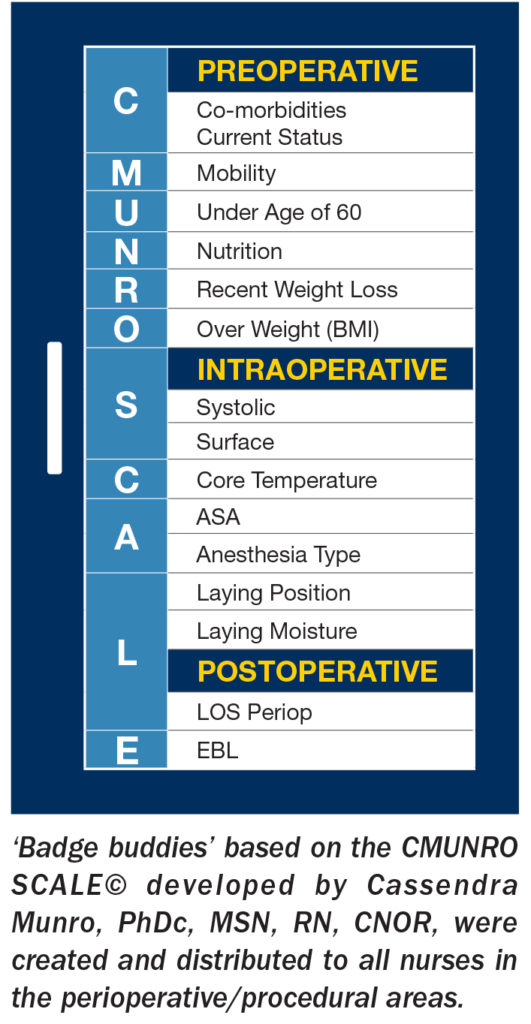

That tool was the Munro Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale for Perioperative Patients (Munro Scale), created by Cassendra Munro, PhDc, MSN, RN, CNOR, Magnet, Professional Practice, and Care Experience Manager at Providence Saint John’s Health Center, Santa Monica, California (sidebar at right). The CMUNRO SCALE© is a mnemonic developed by Munro and supported by AORN for nurses to remember the risk factors evaluated in the Munro Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale. The mnemonic fit the need and became the foundation for our evidence-based skin injury prevention bundle.

That tool was the Munro Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale for Perioperative Patients (Munro Scale), created by Cassendra Munro, PhDc, MSN, RN, CNOR, Magnet, Professional Practice, and Care Experience Manager at Providence Saint John’s Health Center, Santa Monica, California (sidebar at right). The CMUNRO SCALE© is a mnemonic developed by Munro and supported by AORN for nurses to remember the risk factors evaluated in the Munro Pressure Ulcer Risk Assessment Scale. The mnemonic fit the need and became the foundation for our evidence-based skin injury prevention bundle.

Munro’s mnemonic was implemented in the PP areas and used as the sole risk identification tool. Using the CMUNRO SCALE© found in the AORN toolkit, Prevention of Perioperative Pressure Injury, we created badge buddies and distributed them to all PP nurses as a quick reference.

The mnemonic was built into the electronic medical record (EMR) so that nurses at different phases of care could document risk or no risk based on extrinsic factors and comorbidities. Nursing interventions were customized to mitigate risk at each phase of care, and nurses at each stage worked together to provide seamless patient care. If a patient met criteria for three or more risk factors, the evidence-based skin injury prevention bundle was activated.

Munro risk factors for the preoperative area include any comorbidities, mobility status, age greater than 60, nutrition, recent weight loss, and high body mass index. For a patient identified as high risk in the preoperative area, foam dressing would be placed on high-risk areas including the sacrum, heels, and other positional pressure points. Heels would be elevated off the stretcher, and offloading would be encouraged.

By starting the prevention in the preoperative area, patients were protected from the time of admission. Transitioning to the operating/procedural room safely was accomplished with a focused (high-risk area) dual skin assessment that included looking at the areas of skin that could have been compromised in the preoperative area (sacrum and heels). The dual skin assessment also gave the OR nurse a baseline and the opportunity to see any existing skin issues.

The OR nurse did a risk assessment in the intraoperative phase of care and collaborated with anesthesia providers by taking the blood pressure, monitoring the core temperature, and considering the type of anesthesia, positioning, possible moisture, and lying surface. Nursing interventions implemented in the operating/procedural room included applying foam dressing to high-risk areas (based on position and procedure).

The environmental temperature was regulated by maintaining the OR at 68 degrees Fahrenheit and using a forced-air warming blanket. To decrease the risk for facial injury to the prone patient, prone head positioning devices were changed from a square foam headrest to a contoured pressure equalization insert and helmet system.

Intraoperative/intraprocedure micro movements were incorporated into the care. Because micro-moving the patient during a case takes a lot of communication and teamwork, we scripted the time-out to identify the patient at risk and to plan for micro movement. The team would state: “The patient is at high risk for skin injury,” and every 2 hours they would pause and allow for micro movement. The circulator was encouraged to note the micro movement times on the white board as a reminder. At the end of the case, the skin was again assessed, and any injury or abnormality was documented in the EMR.

The postanesthesia care unit (PACU) risk assessment included length of procedure and blood loss. If a patient’s case was longer than 180 minutes and blood loss was more than 500 milliliters, the patient was considered high risk in the PACU, and nursing interventions would continue.

Staff compliance and support have been maintained by peer “skin champions” consisting of two bedside nurses from each phase of care: preoperative, intraoperative, PACU, IR, and cath lab. Each month they review data to gauge efficacy of the process, and they have taken ownership of this project.

Dual focused skin assessment has been built into the nurse handoff at the inpatient bedside. The PP nurse discusses the patient’s position, procedure length, assessment of the high-risk areas, and any injuries present on admission. An inpatient nursing care plan for “at risk for skin injury” has been put into place upon admission based on any risk identified in the PP area. The EMR issues an admission risk alert to the inpatient nurses. Nurses thus can identify risk for skin injury sooner and implement interventions.

Evidence-based nursing interventions based on a validated risk assessment tool have bridged the gap in patient care. The skin-intuitive nurses realize that HAPIs occur in all phases of care; they are not just a care management problem.

Heather Kooiker, MSN, RN, CNL, CNOR, CRNFA, is a clinical nurse leader for surgical services and an RN first assistant at Metro Health—University of Michigan Health in Wyoming, Michigan.

Heather Kooiker, MSN, RN, CNL, CNOR, CRNFA, is a clinical nurse leader for surgical services and an RN first assistant at Metro Health—University of Michigan Health in Wyoming, Michigan.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Never Events. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/primers/primer/3/Never-Events.

Allen G. Evidence appraisal of Chen H, Chen X, Wu J. the incidence of pressure ulcers in surgical patients of the last 5 years: A systematic review. Wounds. 2012;24(9):234-241.